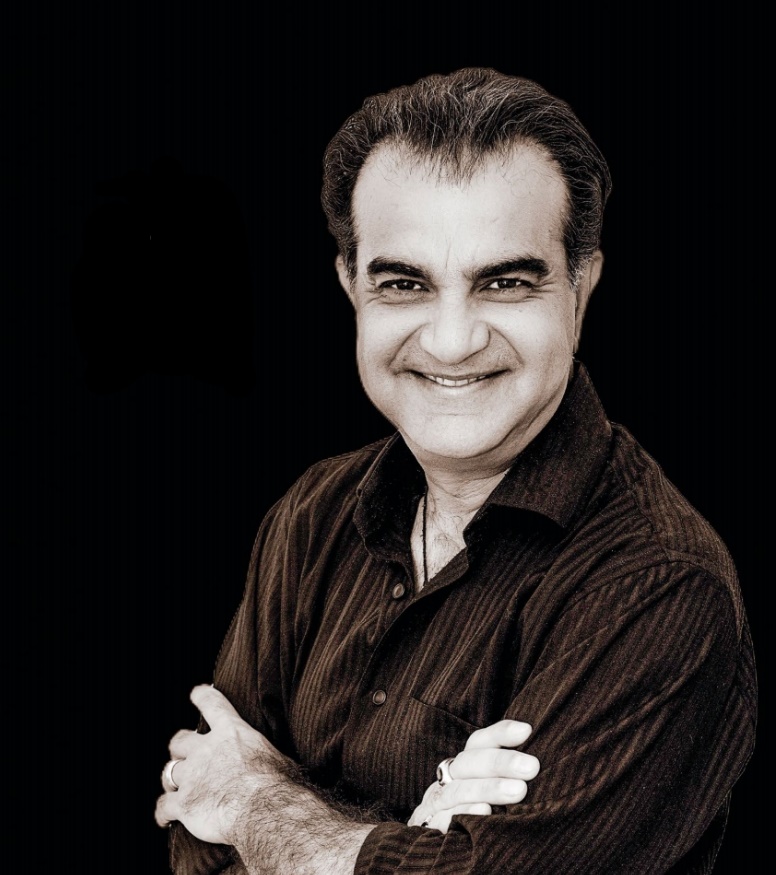

Interview with Vish Dhamija, author of "Prisoner's Dilemma"

on Feb 10, 2022

Vish Dhamija is the bestselling author of ten works of crime fiction, including Unlawful Justice, Bhendi Bazaar, The Mogul, The Heist Artist and Doosra. He is frequently referred to in the Indian press as the ‘master of crime and courtroom drama’. In August 2015, after the release of his first legal thriller, Déjà Karma, Glimpse magazine called him ‘India’s John Grisham’ for stimulating the genre of legal fiction in India. Vish lives in London with his wife, Nidhi.

Ques: Tell us something about your new book Prisoner's Dilemma?

The ‘prisoner’s dilemma’ is a concept in game theory in economics. It demonstrates

that, two entirely rational individuals might not cooperate even if it is in their best

interest. It is so because they do not get to communicate with each other, and

irrespective of how close to each other they are, they end up distrusting their

partners.

In my story, Bipin Desai and Anuj Shastri are two friends who concoct a plan to rob

a van full of cash and manage to get away with a loot of over one crore rupees. The

two are arrested within days, but the cash is still nowhere to be found. Enter Senior

Inspector Arfy Khan, who has only forty-eight hours to make Bipin and Anuj confess

to their crime by convincing one of them to go against the other. The two friends

only have to keep their calm and their stories straight in front of the police. But

there is one major obstacle: Arfy isn’t allowing Bipin and Anuj or their lawyers to

see or talk to each other. It’s all mind games from thereon.

Ques: You’ve been known for stimulating the genre of legal fiction in India.

How’s this new book different from other crime thrillers that you’ve written

thus far?

Crime fiction can cover a lot of subsections of crime. Broadly speaking, it can be

about the crime itself, or the investigation, or when the criminal is brought to the

court for trial. Prisoner’s Dilemma is different as it covers an in-between phase

where the investigation is almost complete and the police have apprehended the

suspects, but are struggling to find damning evidence to charge the perpetrators

with the crime. And the stolen cash is missing. The policeman in the story, Arfy

Khan, is playing mind games with the two suspects expecting either of them to

confess. The story begins after the burglary and the arrest of the perpetrators, so

this novel is neither simply about the cleverness of the heist nor the details of the

police investigation, although I’ve covered those elements to give readers the

complete picture. However, the nub of the story is psychological manipulation, so

whoever blinks first, loses.

Ques: If you were in the shoes of Bipin Desai and Anuj Shastri, would you

choose freedom over friendship?

Clever question. And while it might appear to be simple choice, it is not. It’s not quite

as black and white as one might think it to be. However, to answer your

question—how can I be of any help to my friend if I am not free myself?

Ques: Does the conclusion of a thriller define the quality of the novel?

Not necessarily. I have always advocated that it is not about a happy ending, or any

conclusion for that matter; it is about a good story. The true test of a good novel is:

Is the story interesting enough for the reader (or viewer, as the case may be) to stay

engaged until the end? How you wish to see a story conclude can be different from how I see it. In fact, looking back at the conclusion in one of the books I wrote five

years ago, I now think it should have been different. So your own perception today

might not be the same a few years later.

Ques: Over the years, how have you strengthened yourself as a crime fiction

author?

I read a lot—about 50-60 crime novels a year. And I watch a lot of crime series. One

of the exciting ways to keep stories fresh is to explore various sub-genres: legal and

psychological thrillers, crime capers, heist stories, cozy mysteries, police

procedurals, to name a few. Meaningful subplots also strengthen the story. I also

make it a point to create memorable characters that tell the story. My Rita Ferreira

novels are as much about Rita as they are about the cases she works on. Another

key to making a story exceptional is changing the narrative style—from the first

person to the third person and sometimes a mix of the two. Also, I do not keep to

linear storytelling; I shift the narrative between the past and the present to augment

readers’ interest. There are various other tools to explore and experiment with. One

more thing: research. Always do your homework before you start.

Ques: Your books, Bhendi Bazaar, Doosra & Lipstick, are going to be adapted

into digital series soon. Heist Artist and Unlawful Justice have been optioned

for adaptation as well. What would you like to say about this new

achievement?

It feels great. The fact that my stories can be adapted to screen feels good since the

reach of the screen is far more than that of book. It is an endorsement that they are

well plotted, with believable characters and enough details. Besides, recognition of

any kind is positive reinforcement. It encourages me to write more. However, I’m

frustrated that Covid has delayed the filming, so I’m looking forward to 2023.

Ques: What does it take to pen down a legal thriller?

Be realistic. Granted, it’s fiction, but it needs to be believable. Thirty years ago, you

could have got away without doing the kind of research it requires now. Anyone

with a smartphone and a one-bar 2G-connection can search the web if they think

something doesn’t make sense. Also, talk to lawyers and, if possible, befriend them.

In my experience, all experts are willing to extend help if they think the request is

genuine. I call my lawyer friends all the time. Don’t be afraid to ask.

Ques: What impact do psychological thrillers have on human minds?

None. To clarify, I do not write psychological horror. Psychological thrillers use

misdirection to catch the unguarded reader. Omission is one of the techniques

employed whereby we completely shut out a part of narrative without the reader

realising it. Other techniques often used to misdirect are split time frames or an

unreliable narrator. Trust me, none of these are meant to mess with readers’

mind—they are merely to surprise the readers at the conclusion.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.