Interview With Prochy N Mehta, Author of "Who is Parsi?"

on Jul 25, 2022

Frontlist: As suggested by the title, "Who is a Parsi?" Would you please elaborate on the early development of religion?

Prochy N Mehta: The faith propounded by Zarathustra is considered the most ancient of the revealed religions, but it is also one of the least known. It was earlier known as Mazdayasna religion or Daena or Parsi Religion. To begin with, it is not known exactly where Zarathustra lived or when the Gathas (Holy Books) were composed. The Greeks considered him a very ancient prophet and placed him around 6000 BC. Western scholars place Zarathustra between 2000 and 1000 BC.

Among what is known about Zarathustra’s life is that his family name was Spitama; hence he is often called Zarathustra Spitama. His father’s name was Pourushaspa literally, the owner of many horses, and his mother’s name was Dugdhdova, or milkmaid. They belonged to the clan of the Hvogvas. 11th Century Parsi historian Al Shahrastani gives us the additional information that Pourushaspa came from Azerbaijan, and Dugdhdova from Rae or Ragha in Media (a region of north-western Iran

Theologians and scholars have later shown that Zoroastrian beliefs on reward and punishment, heaven and hell, the resurrection of the dead, the last judgement, the coming of the Saoshyant, a world savior who will conquer evil forever, and in the end, a Renewal of Existence when Man, Nature and all creatures are restored to their pristine glory, were beliefs which influenced Judaism, Buddhism, Islam and Christianity.

According to legends, Zarathustra left his home at the age of 21 to meditate in a cave. He had his first vision of Ahura Mazda when he was 30. The first person he converted was his cousin, Maidhyomaongha. They wandered from village to village for many years, but no one would listen to their preaching.

Finally, the Iranian King Gustasp or Vishtaspa accepted his doctrines and spread it throughout his land and beyond, as he was impressed with Zarathustra’s new doctrine, but the courtiers became jealous of him. They smuggled human hair, bones and nails, and placed them under his bed. In the court, they accused Zoroaster of being a sorcerer practicing black magic. The evidence was produced. Gustasp was enraged and ordered Zarathustra to be taken to the dungeon. At this time, the King’s favourite horse Aspa-siha fell very ill and could not be cured. Zarathustra heard the story and offered to cure Aspa-siha. He laid down 4 conditions before he would cure the horse.

The first was that king Gustasp should embrace the new religion. “O good and noble king, you should be absolutely doubtless of the fact that I am the prophet of Ahura Mazda; you should resolve to be faithful to Ahura Mazda and sincerely follow the teachings of the Mazdayasni Religion,” the prophet said. The king agreed.

The second condition was that the crown prince, Aspandyar, is asked to swear on his sword that he would accept the new faith and spread it throughout the land and beyond. “Will you be ever ready to gird up for any good cause connected to the religion and never turn back therefrom? Will you consider the enemy of the religion as your own enemy?” the prophet asked. Aspandyar knelt before Zarathustra and replied, ‘I will always support the good Mazdayasni Religion with my thought, word and deed.”

The third condition was that Zarathustra is taken to the chambers of Queen Hutaosa or Ketayun, to whom he would explain the new faith, and if she was convinced of its truth, she should embrace it. The Queen replied “Ever since I saw you, my faith in you has been unwavering. I assure you that I will never turn back from the path of Ahura Mazda.”

His last request was for the inn keeper to be summoned and made to tell the truth as to how those articles came under his pillow. Once Zarathustra treated Aspa-siha, he sprung back on his legs and the king was overjoyed. The king recognized Zarathustra as the true messenger of Ahura Mazda and accepted him as the prophet. He exhorted all present to do the same.

Zarathustra married Havovi, the daughter of Frashoshtra who was a senior courtier in Gushtasp’s court. They had three sons and three daughters. The marriage of his youngest and favourite daughter Pouruchista with a man of a different clan is celebrated in the 6th Gatha (Holy Book). He advises the couple “May each of you strive with the other to attain truth.”

The religion preached by Zoroaster is unique in that it insists that each individual must choose between ‘vahyo’ and ‘akem’ or, good and evil mental faculties.

Listen to the noblest teachings.

With an attentive ear.

With your penetrating mind discriminate

Between these two mentalities,

Man, by man, each one for his own self.

Awake, to proclaim this Truth.

Before the final Judgement overtakes you.

-- Yasna 30 Verse

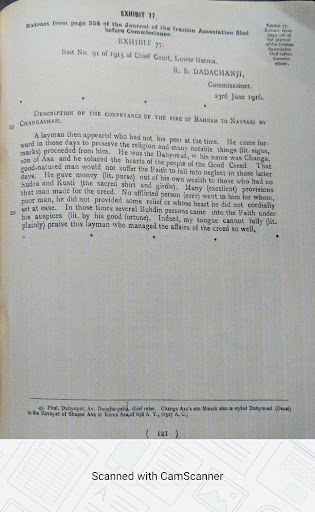

As the Parsis had very few religious texts with them, and it was difficult for them to preserve the knowledge of Avesta and Pahlavi in their new settlements, there arose various questions regarding the finer aspects of the performance of rituals and the interpretation of religious texts. Towards the end of the 15th century, Changasha, the much-respected revenue collector ‘Dahewad’ of Navsari, collected all the various questions on religious matters, and, at his own expense sent Nariman Hoshang to Iran, requesting the Zoroastrians in Iran to answer the list of questions. He presented this list to the Dasturs of Yezd province, who received him cordially and answered all his questions. Nariman Hoshang returned to India around 1478. Thus started the tradition of Rivayats, questions and answers on religion between the Zoroastrians of India and the Dasturs of Iran, which lasted for nearly 300 years.

The Vendidad speaks of the Hapta Hindu, the Vedic counterpart of which is the Sapta Hindu, i.e., the seven rivers of the Punjab. There were 7 branches of the Indus River in India, two of which latterly united, thus giving us the present 5 rivers of the Punjab. The Indian or Hindu name of India should therefore be ‘Sindustan’ and not ‘Hindustan’ which is a Persian name. Dr Modi submitted that the fact was important and suggestive. That even the people of the country should know their country by its Iranian name not Indian name.”

“From some Pahlavi and Persian works we learn King Gustasp of Persia had sent some relatives as missionaries to India to spread Zoroastrianism there. Traditions, recorded in some later books like the Chandragach-nama, the Desatir and Dabistan, support this belief. One Changragacha went to Bactria to discuss the religion. They are said to have made 80,000 Brahmins Zoroastrians. Thus, some form of Zoroastrianism may be traced to India long before the Achaemenians. (The Parsis by Mlle Delphine Menant 1917 Pg 35-37)

The Parsis settled down as farmers and agriculturists, fruit growers, toddy planters, carpenters, and weavers. The legendary British traveler John Ogilby wrote in his famous Atlas of 1670:

“They live here like the natives, free and undisturbed, and drive what trade they please…for the most part (they) maintain themselves tilling and buying and selling all sorts of fruits, tapping of wine out of the palm tree…”

The October 1931 number of the Iran League Quarterly published an article on Parsis in India. It stated, “Parsis are amongst the oldest inhabitants of this beautiful and noble land: for really speaking, they had commenced settling in it since millenniums past, and not only after the fall of the Sassanian dominion as it is commonly understood. Some large bands did indeed emigrate and settle here on that occasion also; but Parsis were known to be in India during the Achaemenian, Parthian and Sassanian times (558 BC-652 AC) as they held some portion or another of this great land as a part of their dominion of those days. Hence it is quite long since they have become true children of the soil; and so, they will love it and serve it with great sincerity and devotion.”

Frontlist: The Parsi community is in decline. According to the National Commission for Minorities, what is the root cause of the Parsi birth rate decline and community extinction?

Prochy N Mehta: “A proud boast of Parsis is that they belong to the world’s most ancient monotheistic religion. As a matter of historical fact, they do. But presently – with the steep decline in birth-rate, the entire community is in jeopardy; it is believed, by many, that Parsi personal law is largely responsible for this plight: which is precisely the theme around which this well-researched and liberally-illustrated book has been written”. Fali Nariman.

In 2011 we were 52,000 strong. With 4 deaths to every birth recorded, we are disappearing. In addition, 50% of all marriages are interfaith. So, we are practically rejecting 25% of the future generation and racing even faster into extinction.

Just as there is no definite answer to Who is a Parsi? there is no definite answer for the decline. Late marriages, no marriages-30% are unmarried, don’t want to have children, put off having children until it is too late, difficulty in conceiving, refusal by most to accept the progeny of interfaith marriages. Thereby accelerating the decline by rejecting 25% of the next generation.

Frontlist: What are your thoughts on establishing prostitution and male legal rights as a Parsi? What would you like to say in this situation?

FRAMJEE CAWASJEE BANAJI1767-1851(HISTORY OF RAST GOFTER)

Prochy N Mehta:

Extract from The Parsees: Their History, Manners, Custom and Religion by Dosabhai Framji Karaka, objecting to the totally immoral behavior of the Parsis:

“The following is a short extract abstract of Framjees minute, from a literal translation of it published in an English newspaper some years ago. The minute was addressed to the members of the Panchayat, and it fully exposes the extent to which corruptions had reached the Parsee community, and the utter apathy and carelessness with which the Panchayat overlooked the unhappy state of things. “I have resolved “said Framjee,” that I shall not join with you in transacting any of the panchayat’s business. Individuals calling themselves Zoroastrians have now become so reckless, that they look upon bigamy and other monstrous sins as anything but sinful. I can site numberless instances of persons in this place, who have not only deserted their lawful wives and joined in matrimony with others, in defiance of the rules of our community, as also of many who are recklessly living and spending their existence in the houses of unprincipled women. You, who call yourself members of the panchayat, will not only take no notice of these affairs, but will allow such sinful persons to participate in all the rights of Zoroastrians, You will not bring such offenders to punishment, but on the contrary, sometimes think very lightly of their offences. It cannot be said that you are not cognizant of this growing evil, and if you do not discharge your trust faithfully, what answer will you give to your Maker on the Day of Judgement.”

See Kholasa-i- Punchayat, edited by Sir Jamsetji.

THE PARSI MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE ACT 1865

In 1865, the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act was passed. Rules and regulations were made to maintain the sanctity of the marriage vows. These laws were made to resolve problems which existed at that time mainly bigamy, adultery, forced prostitution and child marriage. However, adultery was defined as “having sex with a woman other than a prostitute.”

Bigamy was not allowed and any priest ‘knowingly and willfully’ solemnizing such marriage could be convicted. Continued absence of husband or wife for 7 years was made a ground for dissolution of marriage.

Divorce could be granted to any wife on the ground that her husband was guilty of adultery with a married woman, or fornication with an unmarried woman not being a prostitute, or of bigamy coupled with adultery, or of adultery coupled with cruelty, willful desertion over 2 years, or of rape, or of an unnatural offence, or if a prostitute is openly brought into the house to stay in the place of abode of a wife by her own husband.

Divorce could be granted to a husband on the grounds that his wife was guilty of adultery.

Clause 4 of the Act states no Parsi shall after the commencement of this Act contract any marriage in the lifetime of his or her wife or husband, except after his or her lawful divorce.

Mr Fali Nariman in his book Before Memory Fades explains, “Before the year 1865, Parsi Zoroastrians living in India, like all other religious communities, were not enjoined to be monogamous. Men folk could lawfully marry and marry again. But when my mother’s ancestors in Calicut decided to marry again, during the lifetime of his first wife, it was his sons (the Burjorjees of the second generation) who rebelled, and in protest they left home, setting out in a sailing boat,” and landed finally in the port of Rangoon.”

The Law Commissions explanation given for introducing this clause was that “Before the year 1865, when the Act came into force there was no restriction as regards marrying by a person in his or her partners

Regarding the prostitution exemption, the Parsi Law Commission had explained it reasons. It had said ‘Illicit intercourse with courtesans carried on casually and beyond the precincts of the conjugal residence’ was not enough to dissolve a marriage. The prostitution exemption ended at the threshold of the matrimonial home: ‘the gross and flagrant violations of the feelings of a wife involved in the establishment of a kept mistress under the marital roof ought not to be regarded as falling within the just limit of exception.’ It was not the extramarital nature of the sexual intercourse that was the problem but the lack of discretion. All children born of prostitutes were accepted as Parsis.

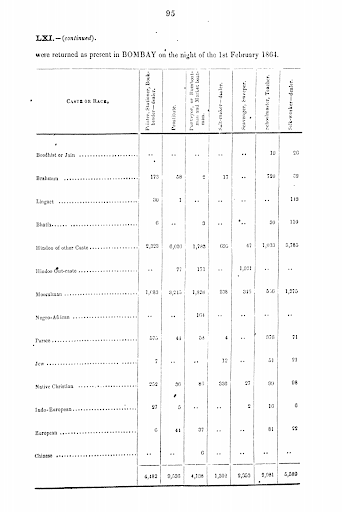

The occupation-wise Census of Bombay in 1864 mentioned 41 Parsi Prostitutes, 4% of the total Parsi female population.

CENCUS OF 1864 BY OCCUPATION LISTED 41 PARSI PROSTITUTES.

The exemption did not exist in the British laws. There, adultery was defined as sexual intercourse with any woman other than the wife. That Parsi Law did not replicate English Law on prostitution reflected a deliberate choice made in the mid-nineteenth century. It was an example of the ways in which Parsi lawmakers did not replicate English law, but pulled away from it, on points that mattered to them.

The fact of the acceptance of Parsi prostitutes and their children was discussed at length in court in both Petit vs Jeejeebhoy and Saklat vs Bella lawsuits as these children were probably born to Parsi women and non-Parsi men.

Until 1936, when the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act was amended, husbands would invariably try to argue in divorce cases filed by their wives, that the other woman was a prostitute. (See Parsi Chief Matrimonial Court4 September 1880; Suit No 5 of 1895; 1893 to 1903 PCMC Notebook, I:215)

THE PARSI MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE ACT OF 1936

This Act replaced the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act of 1865.The bill was introduced in the Council of State in 1935 by Sir Phiroze Cursetji Sethna.This Law was welcomed since it promoted the rights of women. The grounds for divorce were equalized between the sexes, and the prostitution exemption was removed, for the first time a husband’s relations with prostitutes was to be counted as adultery and formed, a basis for divorce. Polygamy was banned. The law states that a spouse could claim a divorce if the partner “ceased to be a Parsi (by conversion to another religion)”. Further it identifies a Parsi as a Parsi Zoroastrian. Compelling a wife to submit herself to prostitution was now forbidden.

In grounds for divorce these following clauses were included:

Clause 32 e) where the defendant has infected the plaintiff with venereal disease or, where the defendant is the husband, has compelled his wife to submit herself to prostitution.

Clause 32 i) that the defendant has ceased to be a Parsi (by conversion to another religion).

What is important to note is that all illegitimate children born to Parsi men and Parsi women, irrespective of who they were fathered or mothered by, have always been accepted into the religion and community. We are all Parsis.

In 1865 and 1936 we were evolving as a community, as people. Our personal laws reflect the way our society was at that time and our attempts to enforce change. These personal laws were at that point in time considered modern and progressive and praised for treating men and women as equal. Yes, we have changed and will keep changing as society progresses as situations change.

Frontlist: The Parsis lacked a personal law and no well-defined rules to govern their lives. Who could be a community member was a hotly debated topic in the 1900s. We'd appreciate it if you could take us back in time and elaborate on the same.

Prochy N Mehta:

Parsis, as a tribe, were living in India among the Hindus till about 1499, when Behdin Changashah rehabilitated them and reminded them of their religion. This is recorded in the history of the Parsis of Navsari (a town in Gujarat where they had settled) and was recorded in court in the Saklat vs Bella lawsuit, a watershed moment in the history of the community. They had totally forgotten their religion and discarded the Sudra and Kusti. Chagashah sent missionaries to Iran to ascertain religious procedures. These were called Rivayats.

It was reported in the Parsi Prakash, “One Nariman Hoshang of Bharuch, was deputed by Changasha to lead a religious mission to Iran.” “the religious mission was organized to obtain clarifications on important religious and ritual matters from the Dasturs of Iran. This mission was very successful and led to several such delegations being sent to Iran over a period of 300 years.” The collection of all such correspondence on theological problems between the two sides then came to be popularly known as the Rivayats.” In the Rivayats from 1516 and 1547, Changasha is addressed as first of the Parsi Behdins. Changasha is still remembered by the Parsis of Navsari among their illustrious dead at all public ceremonies; and the behdin families there of Talati, Seth, and Patel claim descent from him.” (Patel, Parsi Prakash 861-62).

The well- known French traveler and scholar Anquetil du Perron also writes about Changasha “There appeared afterwards at Newsaree a rich Parsi named Changa Shah, a faithful observer of the Zoroastrian Law. He distributed his wealth amongst the poor, provided the Parsis with Koshtis and Sudras, and endeavored to bring back those whom ignorance and troubled had led into many errors to the exact practice of the Zoroastrian law. To succeed in this, he applied to the Dastoors of Kerman, consulting them on different points of the Zoroastrian religion, neglected in Gujarat.”

Rustum Paymaster cites from John Ogilby, a Scottish cartographer, as recorded in Atlas V (1670) p. 218-219. “In the course of time, these settlers forgot their origin, their religion and even their name. At length, the name ‘Persian’ was made to them by some men from Persia who instructed them in their religion and taught them to serve God.”

Even today Parsis have been found, unaware of their ancient religion and following Hindu customs and faith, living in abject poverty in the interiors of Gujrat, and the World Zoroastrian Assossiation is endeavouring to help them.

In 1905 and 1915 two cases came to court Petit vs Jeejeebhoy and Saklat vs Bella. (THIS MARKED IN RED IS VERY INPORTANT)

In the year 1903, Mr. R.D. Tata married a French Christian lady in Paris and brought her to Bombay; he got one of the High Priests of the Bhuggasarth sect (the sect the Calcutta Fire temple instructs us to follow) Dastur Kaikhusru Jamaspee to perform her Navjote ceremony investing her with a Sadra and Kusti; He then went through a marriage ceremony, in the presence of about 60 priests, according to the rites and forms observed by the Parsis. He then claimed that his wife had become a Parsi, who professed the Zoroastrian religion.

IN PETIT VS JEEJEEBHOY in 1905

Prominent members of society, priests and some of the trustees of the Anjuman Atash Behram were petitioners in the Petit vs Jeejeebhoy case. They included:

Ratan D Tata (Father of JRD Tata and a priest of the Bhuggasarth sect of Navsari)

Ratan Jamsetji Tata (son of Jamshetji Tata and a priest of the Bhuggasarth sect of Navsari)

RD Sethna (Trustee Anjuman Behram.)

NN Katrak, (Trustee Anjuman Atash Behram)

Dinshaw Maneckji Petit (founder of the Persian Zoroastrian Amelioration fund)

Rustumji Byramji Jeejeebhoy.

Their plea in court was “a person born in another faith and subsequently converted to Zoroastrianism and admitted into that religion is entitled to benefits of the religious trusts and funds in the management of the defendants”, “ie “becomes a member of the Parsi community professing the Zoroastrian religion.”

IN SAKLAT VS BELLA

Bella was the daughter of a Parsi mother and non-Parsi father. Her navjote was performed by Dastur Kaikobad Aderbad Dastur Noshirwan High Priest of the Deccan and also high priest of our Calcutta fire temple. He is the priest we are authorised by our fire temple trust deed to follow in observing our religious rites and practices. He went from Calcutta to Rangoon to perform the navjote ceremony. A suit was later filed to prevent Bella from entering the fire temple.

Witnesses supporting Bella were:

1)Dastur Jamshedji Dadabhoy Nadirshaw. One of the pioneer students of K R Cama’s Zend and Avesta School.

2)Dastur Kaikhusru Jamaspji , Head priest of Bhuggasarath sect. Priest in charge of Banaji Atash Behram

Banaji agairi in Calcutta, Cama bay agiari, Soda waterwalas agiari, Godiwala agiari

Aden, Lanauli, Lahore and Colombo agiaries outside India. (He performed the navjote of Susaune Brair and then her wedding by Parsi rites to Ratan Tata.)

3) N N Katrak Trustee Anjuman Atash Behram of Bombay etc

4) Dastur Kaikobad Aderbad Dastur Noshirwan, High priest of the Deccan, Calcutta, Madras and Malwa. He had 23 panthaks in his charge

5) Khodeyar Sheriar Irani priest and Son of the high priest of Yazd

6) Professor Ardesher Wadia, Secretary of the Iranian Association and the Zoroastrian Conference.

7) Hormusji Jehangirji Bhabha, Father of Meherbai Dorabji Tata and grandfather of Homi Bhabha India’s foremost nuclear scientist. President of Iranian Association and the Zoroastrian Conference.

In both Saklat vs Bella and Petit vs Jeejeebhoy the High Priests performed the initiation ceremonies and they as well as the trustees of the Atash Behrams went to court to support Bella and Ratan D Tata as witnesses. All these legal documents are now available

The High Priests Dastur Kaikobad and Dastur Kaikhusu Jamaspee of the Bhugasarath sect, who performed the religious ceremonies in both the cases accepted all persons initiated into the faith as Parsis.

However, The judges, while confirming

a) that conversion is a tenet of the religion and

b) that the child of a Parsi mother and non-Parsi father is entitled to be initiated into the religion,

attempted to differentiate between the words Parsi and Zoroastrian by aligning the word Parsi with a) race or b) caste.

Strangely the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act of 1936 does not refer to race or caste at all. This Act finally (I say finally, as the word Parsi has not been defined earlier) identifies a Parsi as a Parsi Zoroastrian. It does not mention race or caste.

Instead, it states there are grounds for divorce- ‘if the defendant has ceased to be a Parsi by conversion to another religion’. Since one cannot possibly change one’s race or caste which is decided at birth, the only interpretation is that as per Statute the word Parsi only identified religion, according to the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act 1936.

In effect “Who is not a Parsi?” is also defined in the Parsi Marriage and divorce Act of 1936. This definition has been used in two court cases. In 1937 in Dhunbai Sorabji Palkhiwala vs Sorabji Ardesher Palkhiwala, divorce was granted as one of the partners had converted to Islam and in Maneka Gandhi vs Indira Gandhi in 1984, it was decreed that Sanjay Gandhi was not a Parsi as his navjote was not performed.

It is indeed strange that today we do not pay any heed to our Parsi Personal Law. Instead, we tend to follow an obiter dictum (observation, no judgement was given as the ladies seeking clarification were not party to the suit) made by a judge in 1905 in which he unilaterally overruled the court recorded statements of our High Priests.

It is even more strange that our present practices that we are told have been sacrosanct from time immemorial, are different from those practiced earlier with the sanction of High Priests and scholars of that time.

It is hoped and expected that during the current 21st century it will get established in Courts of law in India that biologically maternity is as important as paternity to establish even a racial claim to be a Parsi. (FALI NARIMAN)

Frontlist: Dadabhai Naoroji, Ratan J Tata, and others were willing to fight for what they believed, that the terms Parsis and Zoroastrians meant the same thing. What are your thoughts on the matter?

Prochy N Mehta: Though there is so much debate in our small community about the difference between the terms Parsi and Zoroastrian, the interesting thing to note is that the word Zoroastrianism is of recent origin.” The name ‘Zoroastrianism,’ referring to the religion showcased in the exhibition The Everlasting Flame, was coined only relatively recently. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, it first occurs in 1874 in Principles of Comparative Philology by the Oxford Assyriologist The Reverend Archibald Henry Sayce in connection with the religion of the Persians. The term is based on the form Zarathustra, which is the Greek variety of the Iranian name of the religion’s founder, Zarathustra.” (The Everlasting Flame. Exploring Religion, History and Tradition. Edited by Allan Williams, Sarah Stewart and Almut Hintze) The religion from ancient times was known as Mazdayasna religion or Daena or Parsi Religion. In fact, Dadabhoy Nowroji read a paper on the “Parsi Religion” at the Liverpool Literary and Philosophical Society, on 18 March 1861, and similarly Reverend John Wilson wrote his famous treatise on the Parsi Religion as contained in the Zand Avesta in 1843.

Ratan J Tata was one of the petitioners in Petit vs Jeejeebhoy. His plea in court was “a person born in another faith and subsequently converted to Zoroastrianism and admitted into that religion is entitled to benefits of the religious trusts and funds in the management of the defendants”, “i.e., “becomes a member of the Parsi community professing the Zoroastrian religion.” (Petit vs Jeejeebhoy.)

Justice Daver stated:

.”130. The plaintiffs are not content to base their case merely on the ground that the Zoroastrian religion not only permits but enjoins conversion: they go further, and contend that it has been usual and customary amongst Parsis to admit Juddins-that is, persons born in another faith-into their religion. They say that such Juddins, on being admitted into the Zoroastrian faith, became not only Zoroastrians but Parsis; and that such converted Parsis have been always allowed to be carried to the Towers of Silence on their death, and that during their life-time they have entered all places of religious worship, such as Atash Behrams, Agiaries, and Dare Mehers, as a matter of right.” (Petit vs Jeejeebhoy)

“140. The plaintiffs' contentions shortly put are: It is both usual and customary for Parsis to admit Juddins into their religion and give them all the benefits of all religious Funds and Institutions endowed or dedicated for the benefit of their own people.” (Petit vs Jeejeebhoy)

Throughout the book I have used the two words interchangeably . Parsi and Zoroastrian are tautology i.e. they mean the same.

THIS IS IMPORTANT. NOT MANY PEOPLE ARE AWARE THAT INTERFAITH MARRIAGES WERE NOT LEGALLY POSSIBLE BEFORE 1954

The two Special Marriage Acts are mixed up in the minds of most Parsis, who imagine the Act of 1872 is still in force. The laws of India have changed but people do not realise this and hang on to the beliefs which are no longer sanctioned by the law today.

- The Special Marriage Acts caused a lot of confusion. Under The first one in 1872 interfaith couples could register their wedding but would have to make a declaration separating themselves from their religions or convert to the same religion.

A Parsi could marry a Parsi under the Parsi Marriage Act of 1865. Under the Special Marriage Act of 1872 a Parsi could give up his or her religion and marry an alien or the alien could convert to the Parsi religion. Susuane converted and became a Parsi and married Rata Tata under the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act. However, Ratti Petit converted to the Muslim religion and married Mohammed Ali Jinnah. In 1954 a new Special Marriage Act was enacted where for the first time inter-married couples could keep their own religion after marriage. It was only after 1954 that interfaith marriage became a reality and their legitimate children having a choice of religion became a possibility.

Most people are unaware of the change in law which has made interfaith marriage a reality in India.

Mr Nariman advises - Reading the entire judgment of the Single Judge in Jamshed Irani vs. Banu Irani (1966 Vol. 68 Bombay Law Reporter 794) it is quite clear that Justice Davar’s dicta in the Division Bench judgement of 1908 (that “Parsi” was race and Zoroastrian was religion) was not correct – not only in the light of evidence led in the case of Jamshed Irani vs. Banu Irani - but also as extracted from the judgment of Justice Davar (extracted by Justice Mody at page 797 of 1966 Vol. 68 Bombay Law Reporter 794), where an Iranian Priest’s testimony in the 1908 case is referred to which states:

“Some Mohamedans in Persia call us Parsis; some call us Zarthostis. The word Parsis is in common use in Persia. It means Zarthosti. Mussalmans in Persia use the word Parsis commonly to designate our people – the Zarthostis”.

The words “us” and “our people” (in the quote above) refer to the people of Iran.

Frontlist: Please explain why Zoroastrianism is considered a monotheistic religion? Why are Parsis followers of Zoroastrianism?

Prochy N Mehta: This was a much-debated subject in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Parsis having forgotten their ancient religion were living as a tribe amongst the Hindus and following their customs. Through the Translation of the Gathas in the late 18th Century, Parsis learnt that their religion was a monotheistic religion which believed in one God, Ahura Mazda.

Having lived amongst the Hindus for over 1,300 years the Parsis had adopted many of their religious customs. Towards the end of the 18th century noted Indologist Sir William Jones reported similarities between Sanskrit, Greek and Latin. This prompted scholars to translate the Gathas or the Holy Book of the Parsis.

Monotheism is what Dadabhoy Nowroji refers to when he says, “The Parsee Religion is for all, and not for any particular nation or people.” This is what Rabindranath Tagore refers to in his Essay, The Prophet, in The Religion of Man. “Zoroaster was the first man, we know who gave a definitely moral character and direction to religion and at the same time preached the doctrine of monotheism.”

Dr Irach JS Taraporewala translated the Gathas in his book The Divine Songs of Zarathustra, in which he writes, “The place of Zarathustra amongst the prophets is unique. He was born not merely to teach and uplift the Iranian race so many thousands of years ago, but his message was meant for all humanity and for all ages. For Zarathustra was not only the prophet of Iran, but He was the world teacher, and this message is the eternal teaching of Truth, Love and Service. His message has a very special value for humanity.”

Eckehard Kulke in his book The Parsis of India, pg. 93, writes about the Parsi religion, “the actual incentive for a religious revival came from the side of Christianity.: “Since 1825 the Parsis in Bombay found themselves exposed to increasing criticism from the Christian missionaries,” “They were trying to represent Parsism as a natural religion because it allegedly worshipped natural elements.” He says” Parsism was accused of dualism……. the majority of the Parsis subsequently professed a strict monotheism, which still represents the predominant religious doctrine among the Parsis today.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.