In the week of Donald Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, Kehinde Andrews, professor of Black Studies at Birmingham City University and author of Back to Black: Retelling Black Radicalism for the 21st Century (2018), made a video for the Guardian arguing that the west “was built on racism” – that the US was created “in the founding fathers’ image of white supremacy” and Britain’s wealth accumulated through centuries of African enslavement. European enlightenment, he argued, was from the outset a racist endeavour.

The video went viral. The strength of its polemic, presented within the context of Britain’s mainstream media, was thrilling. Authors like Robin DiAngelo and Layla Saad had not yet put books bearing titles such as White Fragility (2018) and Me and White Supremacy (2020) on international bestseller lists. Black Panther (2018) had not yet overturned a century of racist dogma about what could and could not thrive at the commercial box office, and last summer’s actions by Black Lives Matter had not yet made the connection between police brutality in America and the legacies of Columbus, Colston and Leopold II a living-room discussion around the world.

Conversations around race and the deep roots of white supremacy have moved fast in certain circles in recent years, and in ways that would have been hard to imagine before Brexit or Trump. As such, with his latest offering, The New Age of Empire: How Racism and Colonialism Still Rule the World, which builds on that 2017 video and, notably, on the intellectual legacy of Cedric Robinson (author of 1983’s Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition), Andrews doesn’t thrill like he did before – this material feels more familiar by now.

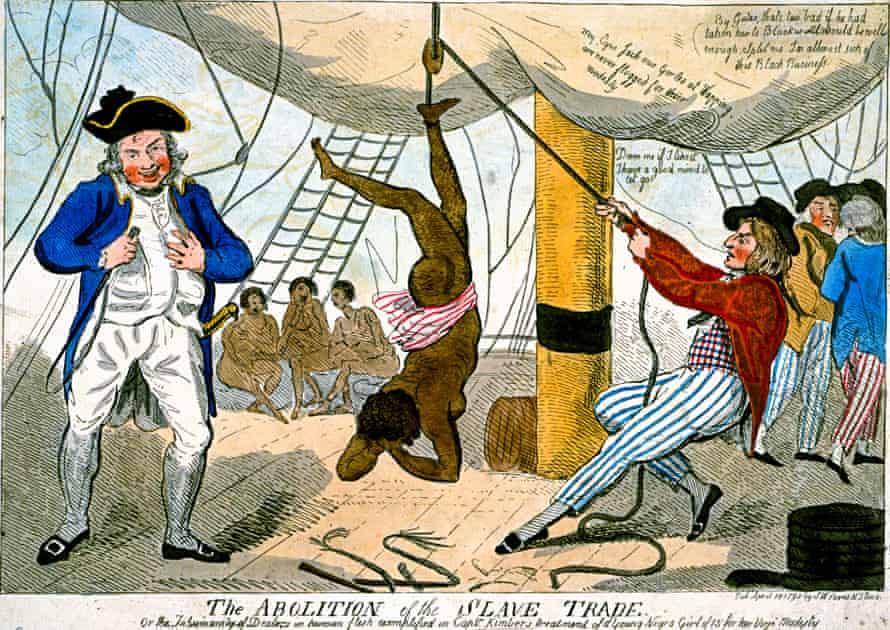

He does, however, provide readers with a solid grounding in the 500-year history of racial capitalism – the enduring significance of the genocide of Native Americans, the transatlantic slave trade and European colonialism – as he works, convincingly, to reveal the “colonial logic and neocolonialism” still at play in the workings of contemporary global institutions such as the UN, the IMF, the World Bank, the WTO. Here, Andrews stands on the backs of giants of black radicalism, from WEB Du Bois to Ava DuVernay, and delivers a book destined to serve as a kind of primary text for a new generation of students of antiracism looking to get to grips with the violence of our imperial inheritance, in broad-brush terms.

It’s not a book without its shortcomings. It reflects but never surpasses its sources; nor does it adequately live up to the promise of its premise, since the “new age” Andrews evokes, focused on a critique of neoliberalism’s transnational institutions, might have felt groundbreaking 20 years ago alongside the publication of Naomi Klein’s No Logo (1999), for example, or Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s Empire (2000), but feels now, in this new era of global crisis, distinctly retro.

Attempts to grapple with more recent geopolitical developments, such as the rise of China or rising global temperatures, feel insubstantial. Crucially, Andrews also fails to deliver on the greater decolonial objective – to not only recount empire’s backstory but to address the question of how we, the mutinous, multiracial descendants of Europe’s enlightenment, from Belfast to Bamako, Los Angeles to Laos, can effectively transcend the violence and sheer injustice of this racist inheritance and create the world anew.

In comparison, and perhaps surprisingly, Sathnam Sanghera’s Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain, points towards the greater decolonial possibility, which he grasps, ultimately, as a “widening and deepening” of self through knowledge, the broadening of horizons and “the understanding and possible adoption of alternative points of view”.

Sanghera’s debut memoir, The Boy With the Topknot (2009), though widely praised for its engagement with the stigma of mental illness and successfully adapted for TV by the BBC in 2017, was also criticised for what writer and critic Kavita Bhanot has described as “its normalisation of white supremacy” – where the cutting of a topknot is framed as an escape from the shackles of ethnic identity, a happy assimilation into the mainstream of (white) British life.

Empireland emerges from a similarly assimilationist motive. Sanghera wants Britons to recognise, with him, their “deep and complex relationship with the world through empire”, to reclaim intimacy with the multiracial nature of a common history.

On that path, he sets out to take in all that, to his “shame”, he’d never known about that history. He attempts to integrate perspectives from writers ranging from those widely deemed to be apologists for empire, including Niall Ferguson and Jan Morris, to those explicitly anti-colonialist, including Pankaj Mishra and Shashi Tharoor.

Thankfully, this intended balance evades him. As Sanghera grapples with details of atrocities, including the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919, and the Tasmanian genocide of the early 19th century, what takes hold, to his own surprise as much as ours, is a sense of moral outrage that in turn disrupts the way he sees himself, his past attitudes, the sense of his place in the world. “My quintessentially British, private-school Oxbridge education,” he writes, “taught me to value western history, western literary forms (such as the novel and the memoir) and western geopolitical forms (the nation state) above their own non-western counterparts, and encouraged me to view my own Indian heritage through patronising western eyes.”

In the wake of personal epiphany, we glimpse with Sanghera pathways of transformative potential. “I may well have been colonised,” he admits. “[But] in embarking on this project, I’m making an effort to decolonise myself.”

It’s a simple but profound response – this searching introspection and a quest for new horizons, combined with a readiness to sit with the contradictions of it all.

• The New Age of Empire: How Racism and Colonialism Still Rule the World by Kehinde Andrews is published by Allen Lane (£20).

• Empireland: How Imperialism Has Shaped Modern Britain by Sathnam Sanghera is published by Viking (£18.99) Source: The Guardian

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.