The realm of Hindi literature is finally being discovered by English Publication in India.

Explore the evolving landscape of Hindi and English literature in India, where bilingualism and translation flourish, shaping modern storytellingon Sep 05, 2023

.jpg)

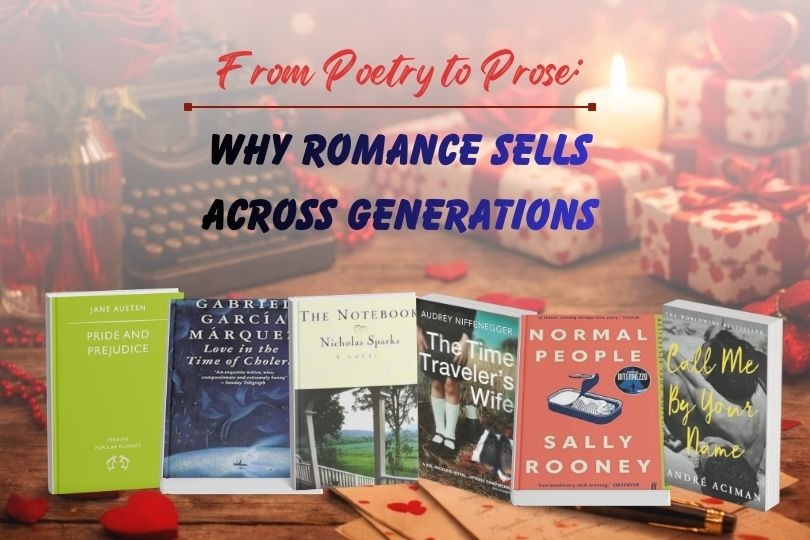

English-language publishers are publishing Hindi literature at an unprecedented rate, and translations between the languages are only expected to increase.

Vineet Gill opted to talk in English 100% of the time when he was in his mid-20s and just started out as a writer a decade ago. Friends and family members would speak to him in Hindi, and he would respond in English as he worked to learn the language, grasp its forms and cadences, and write in it.

Today, says Gill, whose critical English-language biography of Hindi writer Nirmal Verma, Here And Hereafter, was released in 2022. And the reason is simple: today's young writer is much more encouraged to explore and cultivate their bilingualism or multilingualism.

"By following the 'one mind, one language' approach (in my 20s), I was denying myself a wholly different mode of thinking and writing," Gill, 37, says in an interview with Lounge. "Today, there is a greater emphasis on translations, but also on a multilingual—or, at the very least, bilingual—mode even in English texts." Given that reality, I believe that new writers starting out today would do the reverse of what I did."

English-language publishers have started interacting with Hindi literature at an unprecedented rate in recent years. More English-language publications in India are beginning to connect with Hindi—and Hindi literature—in a serious, unironic, contemplative manner, rather than as part of some faddish, ill-informed mission to "Indianise" the page. Publishers have started producing more Hindi books in translation, as well as Hindi translations of best-selling English titles, than usual. In this process, key "bridge" individuals have developed as well—bilingual or multilingual writers who are equally at ease in English as they are in Indian languages, and whose writing in both languages shows this.

The multilingual approach mentioned by Gill can be seen in the work of writers such as Tanuj Solanki. Several stories in Solanki's 2018 book, Diwali In Muzaffarnagar, make it evident (though rarely explicitly) that the protagonists are interacting in Hindi, implying that Solanki is participating in "implicit translation."

"Whenever I am doing implicit translation," Solanki explains, "I am very careful because I don't want the English to draw attention to itself." We normally rate English literature based on its beauty, intricacy, or grace, but when I realise it's an implied translation, I tone it down."

Solanki's most recent book is Manjhi's Mayhem, a "hard-boiled" crime novel in which the protagonist, Sewaram Manjhi, a security guard at a Mumbai café, is introduced on the first page as a man who cannot read or write English; his (first-person) story is ghost-written by his English-speaking journalist friend Ali. Manjhi's enthusiastic declaration of independence from English ("None of this happened in English. The novel's first words ("It couldn't have") are matched only by his amusement at his pal Ali's performative Hindi.

"(...) Credit for this—and a tiny bit of blame for occasionally allowing a Hindi word to remain, I'm told, or for adding a fancy English word where a simpler one would have sufficed—must go to my journalist friend Ali, who does his reporting in English but likes to refer to himself as a patrakaar over beers." This was authored by him."

The "implicit translation" technique would obviously not work for Manjhi's Mayhem because the novel's stylistic tics are informed by the hard-boiled genre's great American exponents, such as Chester Himes and James Sallis (both of whom are mentioned in the novel's Acknowledgements note).

"I had two options when I decided to write the novel in Manjhi's voice: make the 'translation' implicit or explicit." Choosing the former would have meant that my writing training would have set in and I would have toned down the English — which would have been incompatible with the standards of the genre. As a result, I elected to make the translation obvious, making Ali the author of the story."

According to Solanki, linguistic diversity means that certain aspects of the human experience will always be better suited to certain languages. He grew up reading Hindi-language comic books, but his first exposure to literary fiction came through Albert Camus and Cormac McCarthy. There is a dialectic conflict between the Hindi and English "modes" in his novels, which increases the realism of his narratives and provides an exciting case study for multilingual Indian readers.

"There are some milieus in India that the English novel can actually capture really well, possibly better than Hindi, Marathi, or so on," Solanki says. "Things like this will happen in a country with as many languages as India." specific languages will have access to specific patterns of existence—for example, the Versova or Juhu Bollywood novel would undoubtedly be an English novel because everyone in that milieu speaks English."

In India, the debate over Hindi vs. English, or even Hindi vs. Urdu, has been politically charged for both writers and non-writers. Daisy Rockwell's Upendranath Ashk: A Critical Biography (2004) provides a mini-history of how M. K. Gandhi and others exhorted Indian writers (including and especially those writing in Urdu, Punjabi, and other languages perceived as close to Hindi) to write in Hindi in order to boost the nationalist movement and present a united cultural front. As Rockwell pointed out, many Urdu writers agreed to this proposal because they were enticed by the potential of reaching the vast Hindi-reading population in north India and beyond.

"The combination of the linguistic flag with so many millions of fellow Indians, as well as the solid economic possibilities of writing for such a large audience, was enough to turn many writers' heads." What could be better than patriotism and practicality?"

"(Hindi) is an essentially modern literature, not least because the language itself, in its written form, is not more than 200 years old," argues Gill in Here And Hereafter. And multiculturalism has been a part of this tradition since its inception. Bharatendu Harishchandra, a pioneer of Hindi writing, translated Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice into Hindi, among other works.

Premchand drew on a wide range of influences, from (Rabindranath) Tagore to (John) Ruskin, in his writing. The Chhayavad poets were indebted to the British Romantics in both direct and subtle ways. This is to imply that the give-and-take ethos, which is essential to all paradigms of modern thought, is the sine qua non of the Hindi heritage."

Half The Night Is Gone (2019) by Amitabha Bagchi is one of the most innovative and stunning English-language books to come out of India in recent years. Vishwanath, the novel's principal character, is a bereaved Hindi novelist, and his letters provide an intriguing echo to Rockwell's Urdu-to-Hindi argument. In her review, critic Supriya Nair noted that the work sounded like a Hindi novel-in-translation, a trait commended by Rockwell in 2010 while writing on Amitava Kumar's Home Products. "Even Bagchi's slowly unfurling sentences are fashioned to sound like they were translated from modern Hindi, which is both lavishly, almost acquisitively metaphorical, and direct."

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.