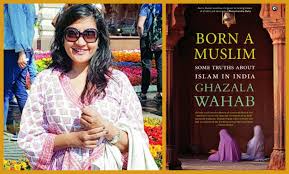

Frontlist | Excerpt: Born a Muslim by Ghazala Wahab

Frontlist | Excerpt: Born a Muslim by Ghazala Wahabon Mar 03, 2021

Ghazala Wahab’s new book looks at how the world’s second largest religion is practised in India. This exclusive first excerpt is from a chapter on the changing face of Muslim society in the country

Training and government policies can subdue prejudices. But once encouraged, they become policies. And this is what is happening in India today, compromising law enforcement and compounding the fears of the Muslims — all this is pushing some of them to take extreme measures such as the reinvention of their identity. A few lower-caste/class Muslims, who are second or third-generation converts, have started to revert to the identity of their Hindu forefathers, starting with a name change. One of them, Mohammed Islam (not his real name), who is engaged in the business of processing bovine hides for leather tanneries in Agra–Kanpur, says, ‘My forefathers were Hindus. They converted because upper-caste Hindus did not treat them well. Islam offered both dignity and security. Now, if Islam does not give us the security, then we can become Hindus again. What will we do with dignity if we can’t stay alive?’

After having denounced idol worship for generations and holding the belief that there is only one God, Allah, can he prostrate before idols? And commit a grave sin, according to Islam?

Looking uncomfortable, Mohammed Islam looks around before answering. ‘It is not that I am not a devout Muslim. I am a Haji (one who has undertaken hajj to Mecca),’ he says, a bit indignantly. ‘My younger son is studying to be a hafiz. But security is also important. It is not just about my life alone, but my family too.’ After a pause, he adds, ‘It is about my business also. If I have a Hindu name, no one will bother that I work with cattle skin. But as a Muslim, I worry every moment.’

‘So, will he only change his name?’

Checking for the umpteenth time about what I was planning to do with this interview, and whether his name would appear anywhere, he finally stammers, ‘I am talking to some people that we want to return to Hinduism. We will go through the reconversion process and change our names. Magar dil mein kya hai yeh kisi ko kya pata (but how can anyone tell what is in our hearts)?’

For people like these, the stakes are very high. From being a daily wager in different tanneries, 20 years ago, Islam started his own business of skin-processing. Now he is a businessman, supplying to tanneries where he used to work earlier. As Professor Amitabh Kundu had noted in his post Sachar report (Post Sachar Evaluation Committee Report), the social mobility of urban Muslims largely pertains to people employed in small-scale industries starting their own enterprises taking advantage of the country’s economic growth, increased demand and easy bank loans.

My younger brother, who has inherited my father’s footwear export business, recalls the time when my father used to run the factory. The profile of the workers then was equally divided between Muslims and scheduled caste Hindus. ‘However, in the last two decades, the ratio has changed,’ he tells me. ‘Today, only 20 per cent of the labour is Muslim. The rest have started their own small factories, supplying to city-based exporters. These are the people who are threatened the most.’

While part of the threat comes from government policies, especially towards businesses that depend on cattle trading — ‘several factories have shut down in Agra in the last five years as they became economically unviable’, says my brother — the bigger threat is the vigilante mob, which now operates with impunity. The labourers-turned-entrepreneurs worry that their former fellow labourers may target them out of professional jealousy. Given the open prejudice displayed by law-enforcement agencies, especially in a state like Uttar Pradesh, small business people are looking at imaginative ways of keeping out of sight.

Not everyone is an activist or has the desire to bring about a revolution. Many people, across religions, prefer leading a regular life without being challenged either for their beliefs or lack of them. And so it is for a large number of Indian Muslims. While they are not unaffected by the Shaheen Bagh protests, they are worried about its impact on their lives and livelihood.

Atika Zakir says, ‘What the women of Shaheen Bagh are doing is really commendable. I hope it has positive consequences for the entire community. But I don’t see the point of aggressive assertion of identity. What good can come out of casting oneself in perpetual conflict with others?’ Atika takes pride in the fact that she hails from a family that embraced modern education three generations ago. Her great-grandfather used to bring out a newspaper called Medina back in the 1940s. A deeply religious family that has been as particular about observing the prayers and Ramzan fasting as about education and employment, Atika says that her family never felt the need to assert its identity.

Read More: Interview: Sharanya Manivannan, author, Mermaids in the Moonlight

Source: Hindustan Times

Book

Born a Muslim

Born a Muslim by Ghazala Wahab

Covid-19

Frontlist

Frontlist Book News

Frontlist education News

Frontlist India news

Ghazala Wahab

Muslim

Muslim society

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(1).jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.