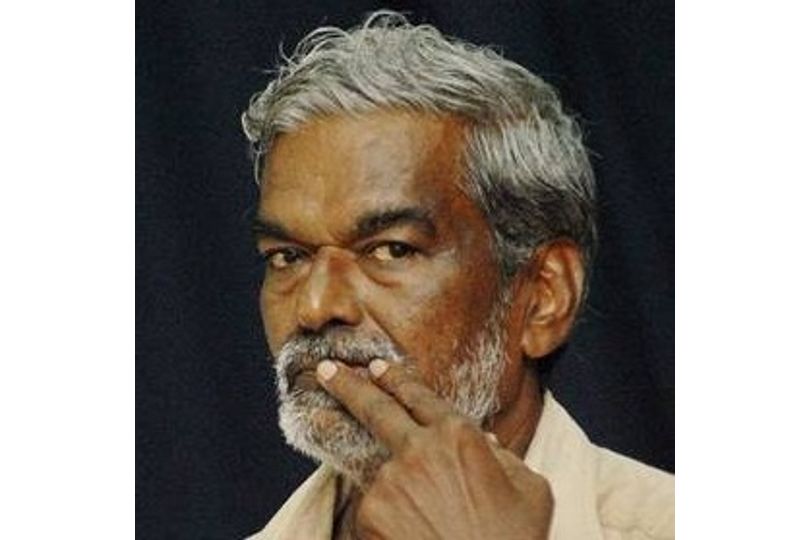

Devanoora Mahadeva, a Kannada author, uses his 68-page book to break the silence and confront RSS

on Jul 22, 2022

We were on our way home after running for office in the 2017 Karnataka assembly election. I went to him and asked, "Devanoora saar," (this spoken,'sir' becomes a kannada term), what's the matter? I was unhappy with a certain candidate from our party and dissatisfied with the explanations I had heard. It's not necessary to be diplomatic. Now you can afford to tell the truth. I am always truthful, he said as he turned around to face me from the front seat of the car. The rest of what he said has eluded me, but this has stuck with me. This wasn't a response, a brag, or a correction. I'll just say it straight up: I'm honest. Just like someone may say: I get up early.

Devanoora Mahadeva is here to serve you, a well-known author in Kannada, a prominent scholar, and a renowned political activist in Karnataka. He is so reserved and humble that you start to question why he is in public life. He has a talent for slipping out of the spotlight. Someone helpfully explains as you unexpectedly notice his absence from the dais: he might have gone outside for a cigarette. Mahadeva is perpetually and infuriatingly late, even by my standards, and a touch disorganised. He does not write with the deliberate carelessness of a bohemian poet. It's just that he lives in a very different way than you might expect a famous person to live and has very different goals.

I should have mentioned that he is Dalit. However, hold off on referring to him as a Dalit author or activist just yet. That would be a grave category error and misrecognition. Despite Shekhar Gupta's genuine, unabashed confidence in the markets, we do not refer to him as a bania intellectual. Despite my outspoken views on caste or reservations, I am not perceived as an OBC intellectual (hopefully). Similar to Devanoora Mahadeva, referring to him as a Dalit intellectual won't reveal much about him beyond his socioeconomic background, the social context in which he writes, and the cultural materials he draws from.

He rejects playing the angry Dalit and restricting his perspective to one group of mankind, in contrast to many Dalit campaigners. He pursues nothing less than the whole truth.

He rejects the traditional division of intellectual labour that has successfully persisted in our time by doing this. The best that the outcasts, contemporary Dalits, and OBCs can hope for is to be their own advocates, in possession of a small amount of the truth. Brahmins are expected to transcend their accidental birth and act as impartial truth-tellers, showing compassion for all people—including Shudras. These roles are disregarded by Mahadeva, who provides charitable interpretation to everyone—including the upper caste characters in his work. His politics include all of humanity and the natural world.

Mahadeva's "honest" criticism of the RSS

Devanoora Mahadeva is making headlines. If your fan club comprises A.K. Ramanujan, U.R. Ananthamurthy, D.R. Nagaraj, and Sheldon Pollock, you don't need an introduction in the Kannada literary circles. But this time, his celebrity has finally reached the Hindi newspapers and other "national" media outlets based in Delhi. He is making ripples with his small book, a 64-page treatise for the modern day.

Over 1 lakh copies of RSS: Aaala Mattu Agala [RSS: Its Depth and Breadth] were sold in the first month after release. There are translations in English, Telugu, Tamil, Malayalam, and hopefully Hindi as well. [Full disclosure: I'm involved with the Hindi version's release.] He chose open source publication in keeping with his belief in decentralisation. The book was published concurrently by several publishers in Karnataka. Students and housewives have pooled their resources to produce their own copies. The author doesn't request any royalties.

What explains this book's sudden success? I went to my friend Professor Chandan Gowda, a sociologist who has a keen interest in Karnataka's cultural past, particularly the socialist heritage from which Mahadeva hails. Given the highly charged communal climate in the state, the timing is important, he claimed. So is the subject: only a small number of authors, even the progressive BJP opponents, are willing to confront the RSS head-on. A spiral of silence can be heard. This frank criticism of the RSS has drawn attention because of this.

Gowda reminds me that the novel succeeds above all else because of the author. Anyone who is familiar with Kannada is aware of Devanoora Mahadeva's sincerity. Everyone is aware that he declined the prestigious Nrupatunga Award in 2010 and the Rajya Sabha nomination in the 1990s. Additionally, in 2015, he returned his Sahitya Akademi and Padma Sri awards. He doesn't write a lot. His entire body of work is only approximately 200 pages long. His speeches are frequently scripted and even shorter than his articles, which he simply reads aloud without making any point. But Kannadigas pay close attention to everything he says. He is not selling his words. You can't make him bend. You can't try to charm him. Even his detractors refrain from criticising him.

However, his truth is not the truth of a data analyst or a historian who bases their conclusions on solid evidence. His criticism of the RSS does not rehash the conflicts between secular ideologies. Devanoora Mahadeva weaves his reality via fables and folklore, through myths and metaphors, and breaks out of the "realistic" jail that had imprisoned much of Dalit literature, as Professor Rajendra Chenni, a student of English and Kannada literature and his old companion, reminded me.

A new language for Indian secularism

He actually accomplishes this in this book. He weaves his message through stories, even though a large portion of the book is about exposing the truth of the politics of hatred — the myth of Aryan origins, the covert plan for caste dominance, the attack on constitutional freedoms, institutions, and federalism, and the economic policy that benefits crony capitalists. In order to stave off a witch who might call on your door pretending to be a relative, folks inscribe these phrases as part of the "Naale Baa" [Come Tomorrow] rite. [The nearest Hindi equivalent I can think of is the saying "Aaj nagad, kal udhaar" written on store counters to deter credit seekers.] The text warns us that screaming demons, who are trying to destroy our civilization, have concealed their prana in a bird seven seas distant (akin to the legend of a king whose life was contained in a parrot). Just as our forefathers did, we must inscribe "nalle baa" on the entrance of our homes.

Devanoora Mahadeva gives the culturally abysmal politics of Indian secularism a new language that is rich in its depth and breadth. As his novella Kusumabale had done with prose and verse, his work bridges the gap between creative and political writing. He does not employ his creative brilliance for political language, to enrich truth through floral embellishment, as is the case with many politically engaged literature. He uses political creative writing as a means of learning the truth. In order to oppose the politics of hate, he does not speak in terms of political theory or high constitutionalism. He communicates with people through their metaphors, language, and cultural memories. Secular politics must now take this action.

Some thirty years ago, my late friend D.R. Nagaraj told me for the first time about Devanoora Mahadeva. He made a fairly subtle comparison between the Dalit literature in Kannada at the time and that in Marathi and Hindi, saying, "Theirs is more Dalit than literary, ours is first literature and then Dalit." Throughout the years, thanks to my relationship and political alliance with Devanoora Mahadeva, I have come to understand the nuances of meaning buried within that statement. I've come to see that the terms "Dalit" or "literature," or their combination, do not adequately describe the political, moral, and even spiritual struggle that Mahadeva's words represent. More than ever, India has to remember Devanoora Mahadeva's adage that "unity is God" and that "diversity is a devil."

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(1).jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.