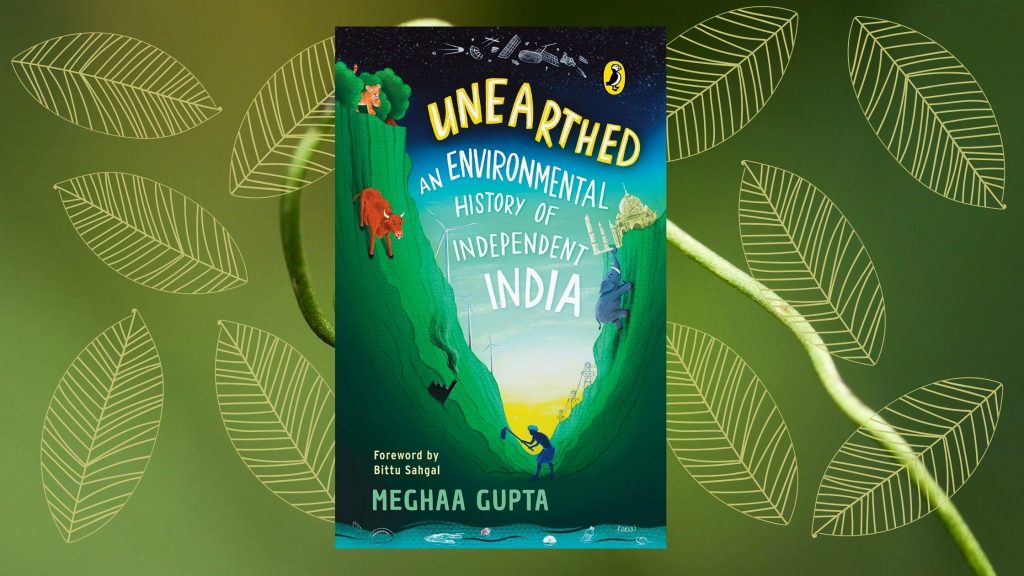

Frontlist | Unearthed: An environmental history of independent India

Frontlist | Unearthed: An environmental history of independent Indiaon Jan 19, 2021

Environmental history from the Green Revolution to climate change

It is daunting to attempt to write on modern Indian environmental history. It is even more so to write for young adults, where it should neither be complicated nor too dumbed down. Gupta has done well in attempting this difficult task through her book. There are two ways of approaching modern Indian environmental history. First is the classical way, beginning from the Chipko movement to the anti-Silent Valley project, then anti-Tehri and anti-Narmada movements and thereon. The second is to place all the elements of the puzzle upfront and try to build a narrative from it. Gupta has chosen the second option in Unearthed. Thus, the book covers environmental issues from the Green Revolution to the National Action Plan on Climate Change. Enroute it discusses the large dams controversy, the White Revolution, tiger conservation, the nuclear debate, elephant corridors, groundwater pollution, urban waste, air pollution in Delhi, renewable energy, space debris and climate change. This book comes at an opportune time, when young people across the world are demanding action from leaders of different countries for dealing with climate change. If the COVID-19 pandemic had not disrupted the Climate Change Convention Conference of Parties (CoP), to have been held in Glasgow in the UK in December 2020, there would have been continuation of the kind of involvement and protest that global youth displayed at the Madrid CoP in 2019. This movement had its echoes in India too. When the seniors in the society, country and group of countries go around in circles, and even backwards on environmental progress, it is natural for the young to become impatient. Protest is the first step, which is then followed by a desire to understand the historical context of the environmental issues in India. Unearthed provides this historical context. Suitably illustrated with sketches and cartoons, and with text boxes with biographical sketches of environmental heroes, Gupta has succeeded in creating a ready reckoner for young adults on how Indians worked to conserve their environment.Multiple options for the readers

The book communicates tricky and controversial issues dispassionately. For instance, it concludes the chapter on the Green Revolution thus: “There are many people who criticize the Green Revolution today. They say it impoverished farmers and damaged our natural environment with chemicals and monocropping. It’s hard to overlook these problems. But food shortage was so acute by the 1960s that without the Green Revolution, India would have suffered a massive famine.” This is commendable, especially when communicating with young adults. Usually the Green Revolution is either praised for increasing agricultural production or criticised for the environmental and equity side-effects it caused. It is good to understand it as an intervention package that was essential for a young republic struggling to feed its growing population, and trying to hold its head high among the comity of nations. It also juxtaposes heirloom seeds along with the seeds of the high-yielding varieties that the Green Revolution produced. Heirloom seeds are those that farmers have conserved from their crops and passed on for planting in their and other farmers’ fields. The book talks about Vijay Jardhari and his Beej Bachao Andolan (save the seeds movement), of Jardhargaon in Uttarakhand, which has collected hundreds of seed varieties in a community gene bank. This group rediscovered the Baranaja method of traditional farming “in which twelve or more crops – a mix of cereals, lentils, vegetables – are planted together. The crops grow in harmony with each other and make the soil fertile over time. The produce isn’t as high, but it’s inexpensive because the farmers don’t need to spend money on buying new seeds, chemical fertilizers or pesticides. Even under unfavourable conditions such as pest attacks or poor weather, the farmers usually manage to get enough produce to feed themselves, their families and their livestock.” Thus by placing the Green Revolution and the Beej Bachao Andolan next to each other, Gupta exposes to the young readers the two options. Both have their advantages and also their limitations. This has a better possibility of giving a nuanced understanding to the young minds, rather than taking an activistic position for or against a technological intervention such as the Green Revolution. Similarly, Unearthed does not fail to mention that the shock of the Bhopal gas tragedy also resulted in the framing of India’s Environment Protection Act of 1986, which gives executive powers to the environment ministry to protect the environment. Unearthed offers many facets, events and developments that together can help construct the modern Indian environmental history for young readers. However, therein lies the flip side – much has been covered at the surface, without going into the depth of the discussions on each of the issues. Perhaps Gupta will do so in her future books. Source: Mongabay

anti-Silent Valley project

Book Review

Book Review Frontlist

Chipko movement

Indian authors

Indian Authors News Frontlist

Meghaa Gupta

Puffin Books

Unearthed: An environmental history of independent

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.