Frontlist | India’s postcolonial bureaucracy & the loss of its ancient marvels

Frontlist | India’s postcolonial bureaucracy & the loss of its ancient marvelson Jan 11, 2021

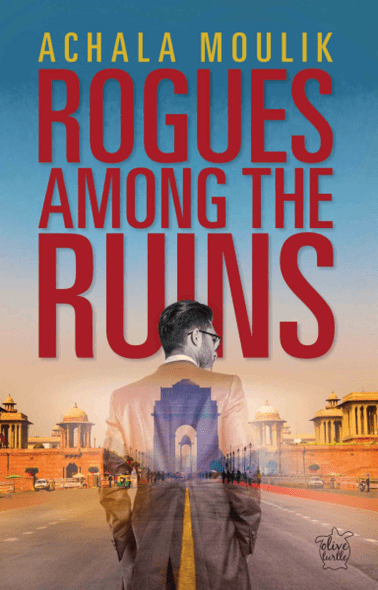

A new book exposes the sordid reality of powerful officials who claim to rule the country.

Achala Moulik, the author of Rogues Among the Ruins published by Niyogi Books, is a former IAS official and was director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India. Her latest work is a riveting fictionalised account, after several prior works on political and cultural history, novels and a play on the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin that was performed in Moscow and St. Petersburg. She received the prestigious Pushkin Medal from the Russian President in 2011 and the Sergei Yesenin Prize in 2013 from the Russian Ministry of Culture. Her new novel is in two parts and the story is complex, particularly towards the end. The underlying theme is the conflict of civil servants who are caught between ideals and their thirst for success. With sardonic humour, sympathy and reluctant respect, the author’s search for truth combines laughter and tears. In the first part, the novel throws a sharply critical light on the deplorable role of India’s postcolonial bureaucracy in not just failing to safeguard the fantastic archaeological remains and cultural heritage but also in actively organizing and participating in the disappearance of a large number of precious ancient artifacts. The distinguished author links the story to the regrettable absence of a proper ethical culture and procedures of accountability in the postcolonial bureaucracy. It is a story on how the Archaeological Survey of India, or ASI, works, and the predicaments of a dedicated but naïve scholar against temptations. The second part is longer—dealing with the scholar’s gifted but morally indifferent civil servant son—and chronicles a later era of political experience. The gifted son encounters, through tawdry dramas and the administrative acrobatics of sycophants and hypocrites, the sordid reality of powerful officials who claim to rule the country. The author takes us on a journey through “Glory Road”, where principles are discarded by the ambitious, the proud encounter humiliations, the idealists are scorned and the stubborn sometimes display the strength overcome ordeals. The lure of antiquity smuggling was apparently a favourite of some archaeologists in the ASI. The morally upright civil servant, in order to prevent cynical exploitation of culture, had to “lock horns with a cabal of corrupt bureaucrats” to uphold “law, justice and Dharma”. In the brilliant Part I, titled “Life Among the Ruins”, the author provides a bird’s eye view of the history and romance of the ASI. In the late 1940s, Dr. Julius Norton, a fictional personality, gives up the prestigious archaeological position he has held in Mesopotamia since the 1930s to become Director General of the ASI in India in the forties. He accompanied by Athena, and commences his seminal archaeological work. Norton is a scholar and a seeker, looking for facts and evidence of civilisations, irrespective of whether his discoveries suit prevailing ideologies. In his view, archaeology is the handmaiden of the quest for Truth. The narrator, Elangovan, the son of an ASI official, explored temples and epigraphical records to uncover the enigmas of India’s past. Raman, his son, is also a man of promise. Norton is essentially a scholar with no imperialist leanings. He would not be happy to be a secret agent of the Raj, but the Viceroy’s secretary would like him to be one. Norton’s perception is that Britain’s imperial mission in India would soon be over, given World War II and India’s freedom struggle. When colonial rule ends in 1947, Norton, as the director-general of the ASI, plans to leave India, though perhaps reluctantly. Elangovan notes the dedication of Norton and Athena over the previous five years, during which they had performed their duties with an all-consuming passion for the 5,000-odd archaeological edifices scattered all over the country. While Indians vowed to save India’s culture, the government lacked the resources to preserve its myriad monuments. Norton impels his staff to select monuments of historical and cultural importance for their urgent conservation. As Norton contemplates a return to Nineveh, he turns messianic. In his farewell speech, he talks about his search for the bicodal text that might provide a clue to the still-undeciphered Indus Valley script. “After that is accomplished, I shall swim across the Arabian Sea and land up in Mohenjo-Daro or Harappa to work on the secrets of the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation,” he says. After he leaves, issues arise at the site of an excavation at the ancient port of Tamralipta—a Buddhist site from where ships had sailed to East Asia—on the coast of Bengal. A cluster of statuettes and an exquisite figurine of a yakshi, or celestial dancer, was taken to an excavation camp, but the other members of the team never saw the figurine again. It is eventually found to have been sold to Sotheby’s in London. Two venerable archaeologists of the ASI are found to have been involved in the sale of the impressive ancient figurines. The author painfully narrates, one by one, the series of systematic misdemeanours and improprieties committed by rogue elements within the ASI after Norton has left. However, a dramatic change occurs when the competent, courageous, and historically-minded Dr. N Sauhrab, who had earlier taught archaeology at a European university, is appointed director of antiquities at the ASI. Sauhrab views Indian history as a “series of challenges and responses that wove India’s national tapestry”, and found that the excavation reports of various historical sites, which could elucidate historical enigmas, had not been written. For example, the Aryan Invasion Theory propounded by Max Mueller needed to be probed. While visiting the Indus Valley site, Sauhrab found many antiquities had been removed by unknown persons. After visiting Kalibangan and Mathura, he speculates that a vast number of sculptures of the Kushana Era had found their way into museums overseas. He feels that if only officers of the ASI had written their reports, we would have known more about the civilisations of the past, from Harappan and Kushan times and even earlier. Some artefacts from ancient Indian sites dated to around the third millennium BC, found in a London museum, could have revealed the bicodal script linked to the Indus Valley civilisation. Dr. Sauhrab felt that the failure to write excavation reports was an unforgivable omission. The author states that eventually Dr. Sauhrab’s integrity, scholarship and insatiable curiosity on historical enigmasled to his eviction from his official position, with the connivance of some in the highest echelons of power. His presence in the ASI was seen as a threat to the massive larceny in the organisation. The mystery of the real identity of Dr. Sauhrab is fascinatingly revealed by the author only on pages 241-242, with all the flair of a detective novelist! Part II of the novel, “Romance among the Ruins”, explores the role of the civil service in the post-Emergency period; the politics of rural development and, importantly, the politics of civil service neutrality, competence and dedication. The Emergency from 1975-77 was an inflection point when governance was weakened and the civil service lost its neutrality and professionalism. The police, in particular, became preoccupied with and was penetrated by politics, which members of the service participated in individually and collectively. Large-scale violations of the rule of law and harassment of citizens who opposed the undemocratic character of the emergent politics were harassed. After 1977, the Shah Commission examined the excesses committed by the civil and police services. The revelations made by the civil servants who testified before the commission highlighted the complicit character of the civil service. The Union Home Ministry produced a report in 1969 which said that unless far-reaching changes are made, the Green Revolution would turn into a Red Revolution. State governments ignored the report and rural development was centralised in government strategy to tackle the emerging Naxalite movement in rural India. The author was in the ministry of rural development in the government of India and had a ring-side view of what kind of rural development was taking place. She was present at an international conference in Rapallo which had prominent Indian participation. She brings out the lack of professionalism on the part of the participating Indian delegation. In another instance, a civil servant of honesty and dedication working in the defence ministry is harassed on account of his earnest objections to a questionable defence deal. The author describes at length the story of this civil servant who seeks to fight corruption in defence deals and his consequent victimisation in matters related to promotion, which led to prolonged legal battles in courtrooms. The honest civil servant ultimately triumphs. The author should be congratulated for her courage and clarity in ably elucidating the dilemmas and challenges faced by the postcolonial bureaucracy in India in this interesting narrative.

Achala Moulik

Authors

Frontlist Book News

Frontlist India news

Frontlist Latest news

Frontlist News

Indian author

Indian Author News Frontlist

Indian authors

new book launch

New Book News Frontlist

Niyogi Books

Rogues Among the Ruins

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.