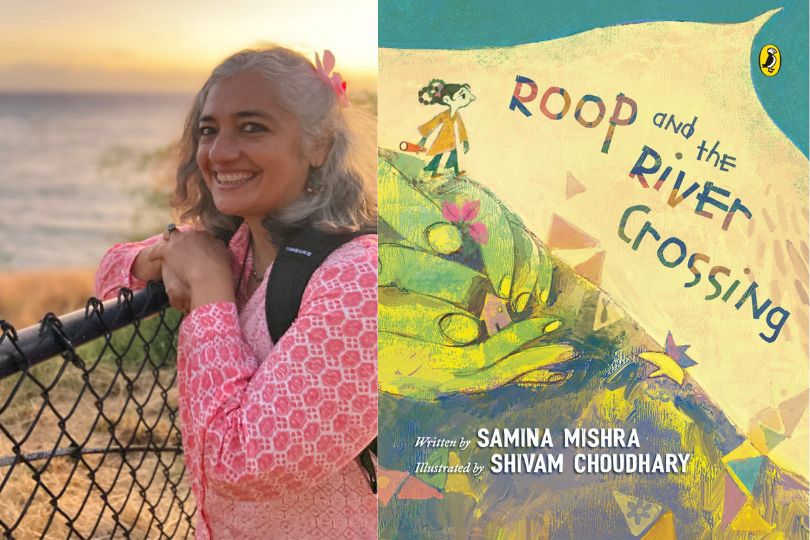

Interview with Samina Mishra, Author of “Roop and the River Crossing”

A moving Partition tale through a child’s eyes, blending innocence, loss, and hope to inspire empathy, resilience, and human connection.on Aug 13, 2025

Frontlist: In Roop and the River Crossing, you depict the Partition through a child’s eyes. What motivated you to revisit this historical trauma through the lens of innocence and imagination?

Samina: My editor, Simran Kaur, at Penguin Random House asked me whether I would be interested in writing something for children on Partition. I had never really thought of doing something like that, though of course, I have read a lot about Partition, and it has shown up in some of my other work, including my very first book for children, Hina in the Old City, which was published by Tulika — there is a bit about Partition in that. I knew it would be very challenging to write about as a picture book, and at the same time, I agreed with her that we need more books for children about this difficult time in our history. Just as children deal with difficult circumstances and issues in the present, they also need to understand our history in all its complexity. This can’t be done in one go — it must happen incrementally, and children’s books can play an important role in making that happen. I guess that’s why I took this one on and wrote Roop and the River Crossing.

Frontlist: The kaleidoscope is a powerful metaphor in Roop’s journey. How did you conceive of it as a narrative tool to explore fragmentation—both personal and national?

Samina: I think there is a bit of a mystery about how ideas come to us, though once they do, we can understand why we held on to them. I have always liked the playfulness of a kaleidoscope and how it changes the way we look at what’s around us. Simran and I had spoken about the idea of a toy that could be a key piece of the story, but I wasn’t sure what that toy should be. I knew I wanted to write a story about a young girl, and I did not want the toy to be a doll, so I just sat with the idea of a toy while I was researching and re-reading material on Partition. The kaleidoscope popped into my head at some point, and I held on to it because it was both playful and lent itself to a metaphorical presence. For a child, it is a toy that encourages seeing and re-seeing, and the way the pieces fall inside and redraw the shapes feels akin to the way the map was redrawn—almost like a toy in the hands of those who carved the land.

Frontlist: Your work often centers on childhood, identity, and memory. How do these themes come together in Roop and the River Crossing to reflect a deeper sense of belonging and displacement?

Samina: I hope readers find their own way to understanding belonging and displacement as they read. For me, while writing, it was the details that evoke the texture of everyday life that were important to think about. I believe belonging comes from the little things that are shared — the food we eat together, the way we play, an incident that is witnessed together — the materiality of the everyday that allows us to make sense of abstract ideas. We respond to these not just through what we do but through how we feel. So, I tried to focus on such small things and the inner life of the child as she goes about her everyday life against the large canvas of a cataclysmic historical event. It’s like there’s a larger narrative arc, and within that are smaller stories that fit inside. So, in the larger story of Roop having to leave her home are the little stories of what she shared — with friends, with the terrace as a space, with the kaleidoscope as an object — that are also the stories or memories she will carry with her.

Frontlist: The book tackles the complexities of Partition in a way that’s accessible to younger readers. How do you balance historical truth with emotional sensitivity when writing for children?

Samina: I think the most important thing while writing for children is not to talk down to them, and it helps to remember the feeling of being a child. If we think of the child as a person with whom we want to share something—just as we do with adults—then I think we ask ourselves the same questions that we would if we were writing for adults. And so, when it comes to things like violence, we have to ask ourselves why we need to write about it, how much we need to show, etc. I don’t think we can hide the difficult things in the world from children—they are witnessing these in their own way.

So, when writing about something in the past, there are historical facts that it is our duty to research before we write about them, and then there are the experiences of historical events, which can be of many kinds. As a writer, I chose the experiences I wrote about based on what I hoped those experiences would encourage a reader to think and feel.

The story of the Pathan helping a little girl cross a river is a documented experience of a girl during Partition, just as there may be other, more violent experiences from that time. I chose the former because it shows us that even in the most challenging circumstances, human beings can hold on to their humanity.

Frontlist: How do you see Roop and the River Crossing contributing to the discourse on patriotism, especially in terms of acknowledging painful histories while nurturing empathy and resilience?

Samina: I hope the book helps readers see that there are ways of connecting with all human beings—if there is a will on both sides. As I say in the endnote of the book: Human beings still struggle to hold on to their humanity, even as the lessons of our history remain unexamined and unlearned. Roop and the Pathan both suffered loss—Roop’s loss was leaving her home, and the Pathan’s was the departure of people—his neighbours, friends, and those he felt a connection to. In these stories of loss are also stories of connection. So, if we remember these stories, can we remain connected to each other?

Frontlist: As someone deeply engaged in children’s media and education, what role do you think literature like this plays in helping young readers understand national identity and historical transitions?

Samina: I think children’s literature, like all literature, needs to reflect the world and the histories woven into our complex identities. Children are part of the world, and though we place the burden of the future on them, we don’t recognize enough that they experience, absorb, and struggle with the challenges of the world just as adults do. Literature can help with that — it can help us see our own experiences differently and enable us to make connections with other lives, both past and present. Just as the struggle to define ourselves — what kind of people we want to be — is an ongoing one, so is the struggle to define what kind of country we want to be. 1947 was not the end of nation-building in the Indian subcontinent. Partition continues to affect lives in India today; it continues to affect India-Pakistan relations. And so, my hope is that literature and stories like this enable us to see that we can find ways of being that foster connection and care, instead of othering and hatred.

Frontlist: How does your work with The Magic Key Centre for the Arts and Childhood influence your storytelling approach, particularly in stories rooted in national history?

Samina: At a time when the world seems full of despair, my work with The Magic Key Centre brings me hope and possibility—by working in collaboration with children and listening to their lived experiences. One of the reasons I write for children is because it affects how I am in the world, especially with children and young people. I believe adults need to be supportive allies for children, and I try to do that through my writing.

I aim to reflect the diverse voices and lived experiences of the children I’m fortunate to meet, so that we can expand the space for children in our public life. I believe there is much that adults can learn from them. I also hope that my writing reflects back to children their own inventiveness, resilience, and wisdom—so that it helps them make better sense of the world.

I write because I believe we need to stop patronizing children and challenge our notions of agency. And because I believe we must always show them hope and possibility—that even in the most difficult circumstances, we get to choose our actions and decide who we want to be.

Frontlist: You’ve worked across media—from books to documentaries. How does writing for children about events like the Partition differ from representing them in film or adult nonfiction?

Samina: I don’t see the different parts of my practice as being in separate silos. Whether I am working on a film or writing for children, the most important thing is to interrogate myself through the process – what do I want to say, why, and how. So, the question of how I want to represent a child is the same whether I am making a film like Happiness Class or writing a book like Roop. Who are the children I include, why do I include them, and how do I show what they are like – I have to ask myself these questions each time. Of course, I think that when writing for children, I tap into my own memories of being a child or the children I know now, so that I don’t end up patronizing them.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.