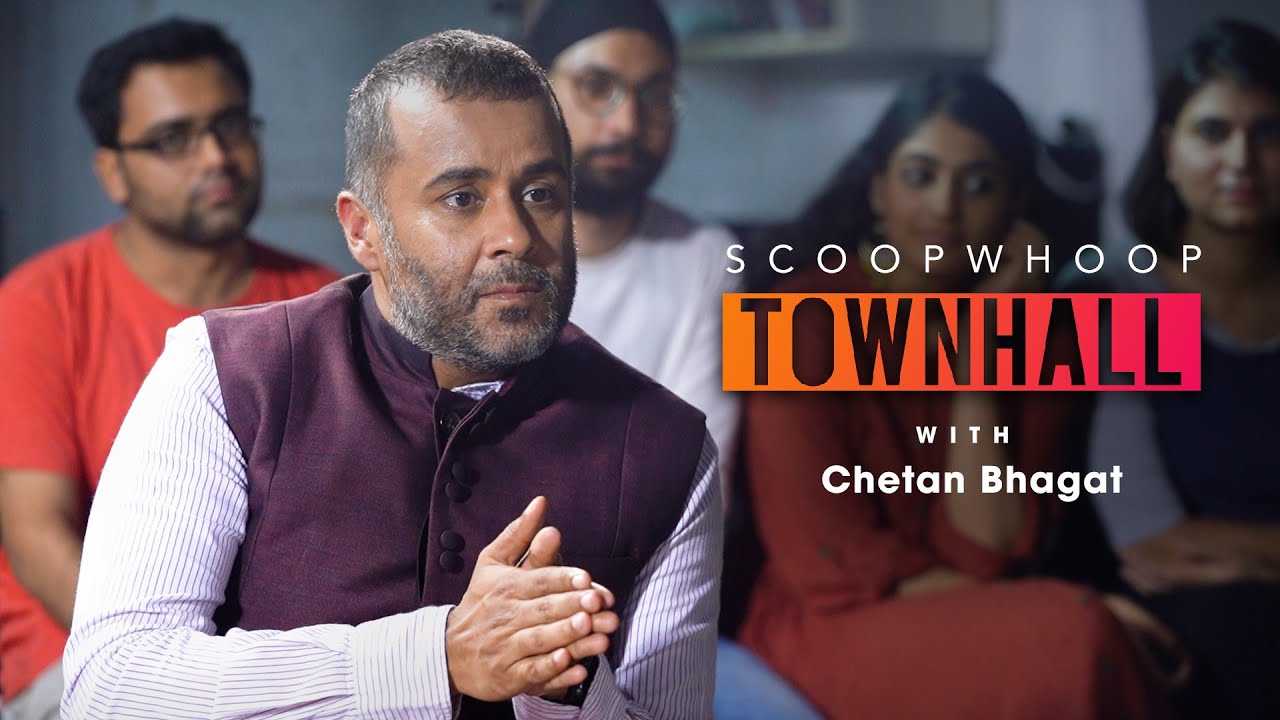

Interview with Atharva Pandit, Author of “Hurda”

Hurda is a haunting debut that blends fiction and reportage to expose rural misogyny, caste, and justice through a chilling crime involving three girls.on Jul 29, 2025

.jpg)

Frontlist: “Hurda” is a chilling and complex debut that tackles misogyny in rural India. What compelled you to tell this particular story, and why through the lens of a crime involving three young girls?

Atharva: Thank you for your kind words about Hurda. To be honest, I am still not sure what compelled me to write about this particular incident. I mean, I know the immediate trigger was a Sunday feature by a reporter called Smita Nair, in The Indian Express. It was a terrific piece of journalism, and I was very affected by it. So I started following the case, reading up on every little detail about its progress. But such stories remain front-page news only for so long, and once they have served their purpose, they become part of history—as indeed happened with this particular incident. But while that infuriated me, it also intrigued me—what place does violence have in our daily lives? And what does it tell us about ourselves, and the society we have developed, when heinous crimes of such mind-numbing violence become just another day of life, just another case, just another story? These things disturbed me, and perhaps that’s what fuelled my fascination and investigation of the story. But why this particular story? I am still not sure. I wrote Hurda to answer that question for myself, but I don’t think I have been successful in that aspect.

Frontlist: The structure of Hurda, told through multiple voices, feels both chaotic and deliberate. What were you trying to achieve with this fragmented storytelling approach?

Atharva: I have always loved reading books with multiple narrators. It creates an effect of cacophony, as if the book is actually alive and breathing with all the voices of its characters. It has this feel of people jostling for space. I love that feeling, because such books, more often than not, are untidy in their structure. They are chaotic, as you have put it rightly, but their chaos has a structure of its own, which builds up as you go on writing. The Savage Detectives, a long romp of a novel by this Chilean writer called Roberto Bolaño, was my first exposure to a multiple-voice novel, and I enjoyed the experience immensely. It remains one of my absolute favourite books, and I wanted to see if I could apply that kind of structuring to a murder investigation, where truth is of utmost value, but where truth also has different versions, making it extremely elusive.

What, really, then, is truth? What do all the facts combine to tell us? Those are the questions confronting both the official investigators on the case, as well as Chitranshu, the journalist who is trying to find out what exactly happened to the sisters on that fateful day — and who did it. But when they realize that truth might, in fact, be impossible to determine, they react in different sorts of ways: the investigators abandon the effort,

while Chitranshu seeks solace in a fictional conclusion. Yet, nobody has come away with any kind of concrete truth — and that’s the point.

Frontlist: Based on a real incident, Hurda walks a fine line between journalism and fiction. As a writer who has also worked in reportage, how did you navigate that boundary?

Atharva: I have always wanted to write fiction, and I have always been writing fiction, ever since I can remember. Writing fiction came to me naturally, but I was also lucky in that I have always also been interested in journalism. Particularly the long-form reportage, which more often than not also concerns itself with stories of humans—humans winning and humans erring. In fact, the Polish school of reportage, which has veteran proponents in Ryszard Kapuściński, Hanna Krall, Melchior Wańkowicz, and, more recently, Wojciech Tochman, is this curious blend of subjective journalism that uses literary techniques to tell a true story. Much like today’s true crime, except that the Polish reporters were doing it much before it became a sub-genre. I was very influenced by those reporters and their work, and I used to dream of writing like them. I suppose I tried to make that dream into a reality in Hurda, although Hurda, I must add, is completely fictional.

Frontlist: Humour and horror co-exist in your novel. How did you use satire and absurdity to sharpen your critique of caste, patriarchy, and small-town morality?

Atharva: I personally think daily life is full of humor, as it is also full of horror. I was merely trying to mirror that in the book. The way we live life, every single day, in itself is absurd. It’s really strange when you think about it: the meaning of existence and all that. The only way to accept that is by resorting to humor, which is also true of the horrors of our society: all these structures that we have made, all these hierarchies, all this malicious ill will that then manifests into a certain kind of violence. It’s so unbearably vicious that the only way to confront it is by resorting to humor, because we should all be laughing at ourselves for what we have become, for what we are. That said, I wasn’t going into the novel thinking that it would be that way — the book revolves around an extremely dark event, but when you observe carefully, even during the darkest of our days, there is always an element of humor present. Because that’s how you cope. That’s how you learn to live. By laughing at the horrors.

Frontlist: In Hurda, women’s lives are constantly being surveilled, judged, or dismissed. What conversations were you hoping to ignite about the way India treats its women, especially in rural contexts?

Atharva: I don’t know if I was looking to ignite any conversations, but it’s a reflection of what I have seen and observed all around us, as I am sure many have. How women are treated, judged, and surveilled in Hurda is actually not revelatory: it’s ever-present. That’s what women go through everywhere, in different capacities. The manner in which they are constantly under the lens might be different in cities than in rural areas—geography makes it more intensely personal in villages like Murwani, where everybody knows everybody else—but it’s not as if cities are havens, I think. That was also one of the things bothering me: the way people react to rape and sexual assault depending on where it happens. There are so many layers to whether or not victims can have justice in India—and it begins, of course, with gender. Then it moves on to caste, religion, space, the location of the victim within that space, and so on. The three sisters, in a way, were at the very bottom of that pyramid—which, ironically, made them into a “story.” And yet, how did that help the cause of the case? Zilch. It languished and remains unsolved.

Frontlist: As a debut, Hurda feels bold and uncompromising. Do you feel it received the attention it truly deserved from the Indian literary landscape?

Atharva: When Hurda was published, I thought it would be read by a couple of people, mostly people I know and people who know me, and that would be it. But it did have a journey of its own, and I was lucky in that most fiction published in India doesn’t receive as much attention. This was all thanks to the initial readers, who wrote about it enthusiastically on social media platforms and in digital dailies and magazines, and convinced their friends and acquaintances to pick it up. It’s heartening when that happens—and I was also invited as a speaker to JLF, which, in the literary world, seemingly means you have made it! I am just kidding. But it’s a huge opportunity, and I am glad for it. At the cost of coming off as ungrateful, I would still say the newspapers were very apathetic towards the book—none of the HTs and Mints and IEs thought Hurda deserved any kind of space in their hallowed pages. But perhaps those pages are reserved for better books—the Booker winners, maybe, or the Indian books which have UK and US deals, perhaps. Who knows?

Frontlist: You were a South Asia Speaks fellow in 2021. How did that experience shape your voice or refine your narrative when writing Hurda?

Atharva: South Asia Speaks came to me at a time when I was very unsure about my fiction-writing abilities. Getting selected for the fellowship, and getting to work with a writer as accomplished as Prayaag, was truly an enriching experience—I couldn’t have asked for anything better. Prayaag was always patient, and incredibly perceptive in his feedback. But he was also a fun mentor—we would write to each other about the books we were reading, or have read, and the books which we loved, the books which did not work for us—and why they didn’t. It wasn’t as if Prayaag would come online and “teach” me writing, he had his own way of going about it, which was to tell me where I needed improvement, and what can be done better, but never asking me to do anything specific. He gave me the room to experiment and engage with my story my way. That certainly helped—and the fact that SAS has grown into such a vibrant community, with over half-a-dozen published and acclaimed authors, is a testament, of course, to its vitality.

Frontlist: Six years after the crime, a journalist returns to uncover the truth. Is this character a reflection of your investigative instincts, and what does their disillusionment say about modern India?

Atharva: I hope I was a better investigator than Chitranshu, the journalist! But our motives are different. Chitranshu goes there to find a concrete conclusion; I went to the village with very clear objectives: I knew what I wanted, and I knew what I didn’t want. What I wanted was to just take in the atmosphere of the place where the real-life crime happened, to understand the language spoken there, to understand the way people live and engage with each other there, and to do all this without intruding or drawing much attention to myself. And what I didn’t want was to be this journalist-turned-investigator who thinks he can swoop in and solve an unsolved crime — which is what Chitranshu wants to do. So yeah, Chitranshu is based on my own persona, I think, but there are also some key differentiators. Or so I hope. As to what their disillusionment says about modern India: I think it just makes it that much clearer to Chitranshu, and certainly to me, that despite all our chest-thumping about the apparent progress and virtues of our society and our systems, concepts of justice and law are still matters of position, standing, class, caste, religion, and, more often than we think it to be possible, mere fluke. Those wheels either turn for you or they don’t, and you cannot do anything much about it either way.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(1).jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.