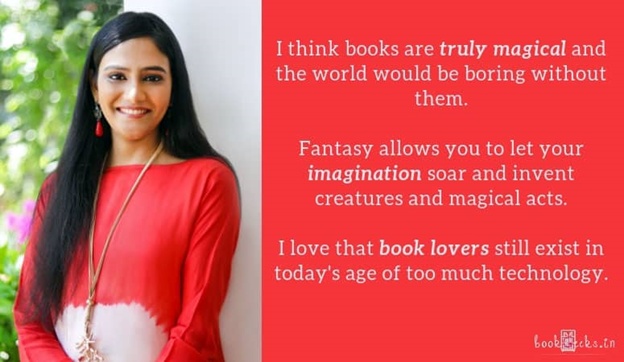

Interview with Aditi Krishnakumar, Author of ‘The White Lotus’

Aditi’s The White Lotus explores grief, resilience, and rebirth through a young widow’s journey in 1900s Tamil Nadu where courage meets tradition.on Jun 23, 2025

.jpg)

Frontlist: At just fourteen, Aru's world turns dark - yet The White Lotus blooms as a story of resilience. What inspired you to write about such a painful topic through the lens of courage and hope?

Aditi: The loss of loved ones and the attendant grief are a sadly universal theme. As much as we’d like them to be, young people aren’t exempt. Sometimes, and I know this from experience, the death of someone close to you – and this needn’t be a spouse – can make it seem, just for a short time, like the foundations of the earth have been shaken.

To me, the hardest part of loss is that moving on can seem wrong – as though, in learning to be happy again, in celebrating small joys, in allowing violent grief to fade into gentle nostalgia, you’re being disloyal to the memory of the person who’s gone.

But the truth is that, the deeper the desolation, the greater the courage it takes to rebuild your life – and that rebuilding is not only normal, but necessary. The best thing we can do in the face of tragedy is to live with authenticity and hope. We owe it to ourselves to find a way to be happy.

Frontlist: The SunLit theme celebrates stories that cast light on overlooked lives. Why was it important for you to tell a story centred on a young widow in early 20th-century Tamil Nadu?

Aditi: I’ve grown up hearing stories of my foremothers: my great-grandmothers, some of whom I was fortunate enough to know, and my great-great-grandmothers. It always seemed like what people remembered most about them was their resilience, their robust common sense, and their practical, problem-solving approach to life.

Of course, that’s them as adults. I don’t know what they were like as children and teenagers. I can only imagine that they were like most young people: full of dreams, eager for the future, and almost certainly emotional and immature on occasion.

Some of the stories also included relations who were less fortunate. An orphaned nephew or a widowed sister-in-law, people left with nothing, would definitely be taken in and provided for. But they would always be aware of their dependent status, and expected to show suitable gratitude.

All that came together in The White Lotus. How would a young girl in the early 1900s have coped with sudden loss – the loss not only of a loved one, but of all her hopes? Would she have been doomed to go through life as a helpless widow? I like to think not, that she would have found a way through her grief into a new and fulfilling future.

Frontlist: Aru begins the story powerless but slowly discovers agency. How did you approach her transformation, and what do you hope young readers take away from her journey?

Aditi: There are two messages that I hope young readers take from the book. One is that sometimes life doesn’t work out exactly the way you planned. But that doesn’t mean you have to give up on your dreams – you may just have to think harder about what your dreams are and find new ways to achieve them. In the end, that might be more meaningful.

The other, to me the more important, message, is that ultimately it’s up to every person to decide who they’re going to be. You can’t control what other people think, or say, or do. What you can control is who you are. What stands are worth taking, for you? What’s

just irrelevant background noise, for you? I think answering these questions is an important step in discovering your own agency.

Frontlist: The stolen jewel, the goddess’s wrath, and the village whispers create a layered atmosphere. How much of this was inspired by folklore or real stories from rural India?

Aditi: The general setting and the atmosphere were very much inspired by the rural India I’ve known. When I was a child visiting my grandparents’ villages, if I happened to wake before dawn and slip out onto the terrace, I’d hear people singing as they went to work in

the fields. That singing gave me the shivers the first time I heard it in the half-light – and it remains to this day some of the most atmospheric, haunting music I’ve heard.

I’ve tried to recreate that atmosphere in the book – I think that’s why Arali does so much of her writing at twilight or at night with a kerosene lamp.

Stolen jewels and vengeful deities are folklore staples. There’s something about them that appeals to us, because however rational and logical we try to be, there’s a primal part of us that wants to believe in them. And I think that matters – whether or not a diamond is really cursed, the fact that people believe it is might turn a story into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Frontlist: You’ve said your author bio is fictional fun. But this story is rooted in very real pain. How do you move between the imaginative and the historically grounded in your storytelling?

Aditi: When you’re writing this specific kind of historical fiction, where the period and general location are real, but the characters themselves are imaginary, it gives you a lot of freedom. I’ve been fortunate in being able to spend time with older family members, and

the homes they grew up in – that gave me a great sense of the setting. And of course I had fact-checking help for the period details. You have to do your best to be accurate there.

With the people you make up, you really can let your imagination run riot. People are people, in any place and at any time – and people are all so wildly different from each other, so unique in themselves, that anything is possible. Was widow remarriage generally frowned upon in 1901 Tamil Nadu? Yes. Would most people in Arali’s village have expected her to fade quietly into the background and stay there for the rest of her life? Yes. Were there people who believed that women had rights and would try to help Arali gain hers? Also yes.

In the intersection of all that, it’s possible to find a fascinating story.

Frontlist: The grandmother Aru cares for becomes an unexpected ally. Can you talk about the intergenerational bond they share and how it becomes a source of light in Aru’s life?

Aditi: In some ways the grandmother Aru looks after becomes a proxy for her own grandparents, whom she’s never known. And yet it’s not exactly the same, because despite the constraints on women in the early 1900s, the landlord’s mother will always have known a degree of power and freedom that Aru’s family couldn’t have imagined.

It’s a relationship that’s good for both of them. The grandmother is lonely, and Aru gives her both care and companionship. The importance of that can’t be overstated; we see all around us the difficulties of isolation, particularly for older people.

The grandmother’s life experience is very different from Aru’s – and of course far longer. She’s learnt to ignore the background noise and focus on what’s important. That can be hard to do, especially when you’re young, and that’s something Aru learns from her. Although there are several other people involved in her education and future prospects, the most important contribution is the grandmothers: she’s the one who encourages Aru to stop thinking of herself as a widow and begin seeing herself as a woman.

Frontlist: Did your experience living abroad influence the way you approached writing about India’s past and its social complexities?

Aditi: I think it made me more careful. I’ve lived abroad for several years, and also lived in India for several years: that makes you really aware of the dangers of painting all of India, or all the past with a single brush. Also, while this book had folklore elements, I absolutely didn’t want to portray India as a magical land of snake charmers.

As an Indian, I’m very much aware that you can’t hope to capture all the social complexities of the country in a single book – an encyclopaedia wouldn’t be enough! But

that doesn’t mean you can’t write a story set in India’s past that’s real and authentic. The key is, I think, neither to sugarcoat the past nor to see it as some sort of unenlightened dystopia.

Every writer of historical fiction finds that balance somehow – perhaps having lived both in India and abroad has helped me find it in my books.

Frontlist: The White Lotus grows in the mud, symbolising purity in adversity. Why did you choose this as the title, and what does it mean in Aru’s context?

Aditi: I’m actually not great at book titles. Part of the reason I never have chapter titles is that I can’t fathom having to come up with sixteen or so headings – the main titles are hard enough!

But The White Lotus just seemed to fit. I didn’t have a proper working title for the book – I named it just before I sent the first draft off to my editor. We had a lengthy debate about it and we considered a lot of different titles, but we always came back to this one.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_(1).jpg)

.jpg)

Sorry! No comment found for this post.